There’s one animal we always go particularly hog wild for at RWS! This month, we’re celebrating Virginia’s most spud-like species: the mighty helpful groundhog.

Groundhogs are consistently a staff favorite species to work with. As the only area rehabilitation facility that treats orphaned groundhogs long-term, we end up receiving many of them each year. Our groundhog patient count is up to 10 already! Though these corpulent fuzzballs can be controversial amongst gardeners, we hope this Critter Corner will help folks find a new appreciation for these ecological superheroes.

Groundhogs go by many (very charming) names. Their Latin name, Marmota monax, refers to their marmot relatives and to the the Algonquian name for groundhogs (Móonack), meaning “digger.” Colloquially, though, groundhogs are also called woodchucks, groundpigs, whistlepigs, weenusks, land beavers, and thickwood badgers. Try to say that last one three times fast! 😂 It’s fitting that their offspring also go by many monikers, including kits, pups, chucklings, and our favorite at RWS: hoglets.

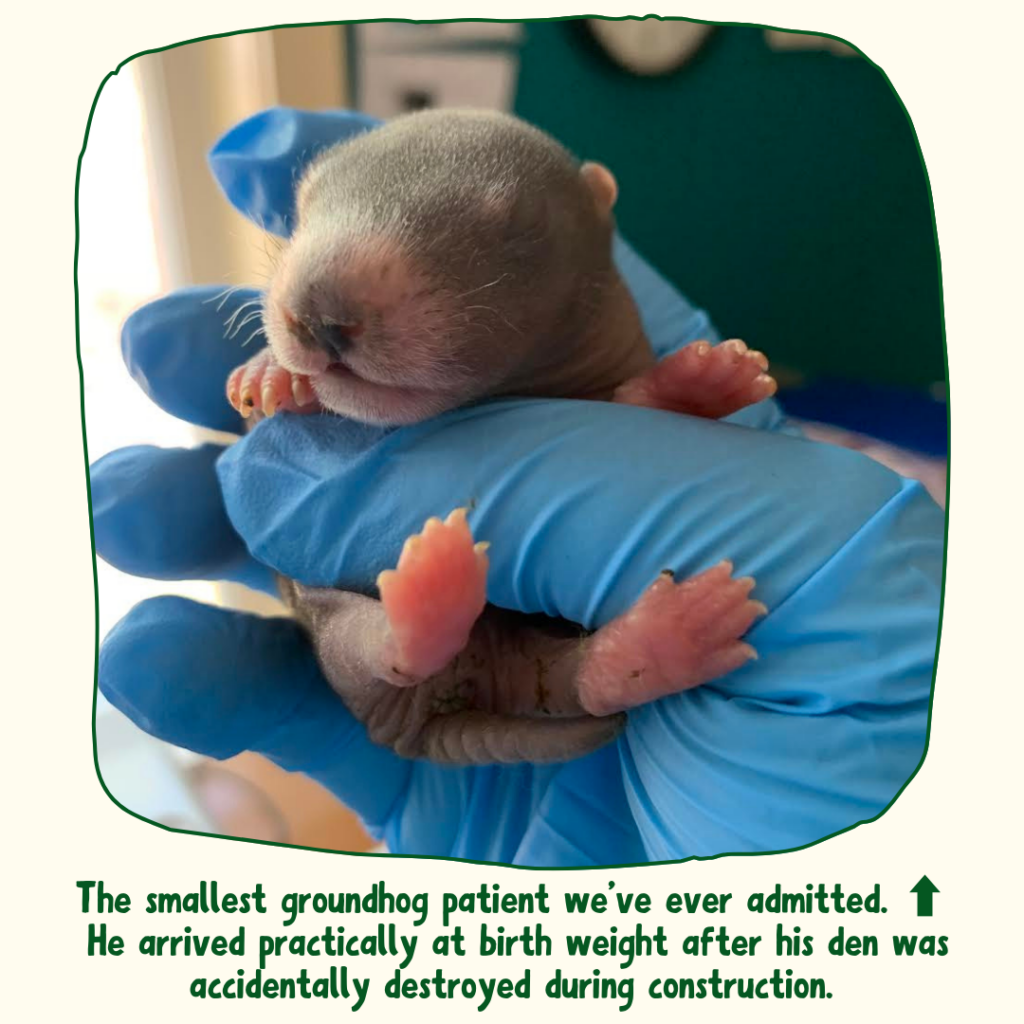

And boy, is it hoglet o’clock around here! Hoglets are born in April and May each year here in Virginia, most often in groups of three to six. They are born naked, with their eyes and ears sealed shut, receiving constant care from their mother deep inside her burrow. The male usually leaves the burrow to find another mate shortly before the female gives birth and does not typically return. Scandalous! 😮

And boy, is it hoglet o’clock around here! Hoglets are born in April and May each year here in Virginia, most often in groups of three to six. They are born naked, with their eyes and ears sealed shut, receiving constant care from their mother deep inside her burrow. The male usually leaves the burrow to find another mate shortly before the female gives birth and does not typically return. Scandalous! 😮

Recent research has shown that groundhogs, long thought to be very solitary, may be much more social and family-oriented than we thought. Cue the “awwwws!” By August, the spring’s hoglets begin to separate from their mother’s den – but they’ll usually begin to create their own burrows not too far from their original birth site. In fact, some mothers may pass on their den to a female offspring! From there, groundhogs may establish and live in large, interconnected “clan” groups – whole networks of nuanced, kinship-based social systems.

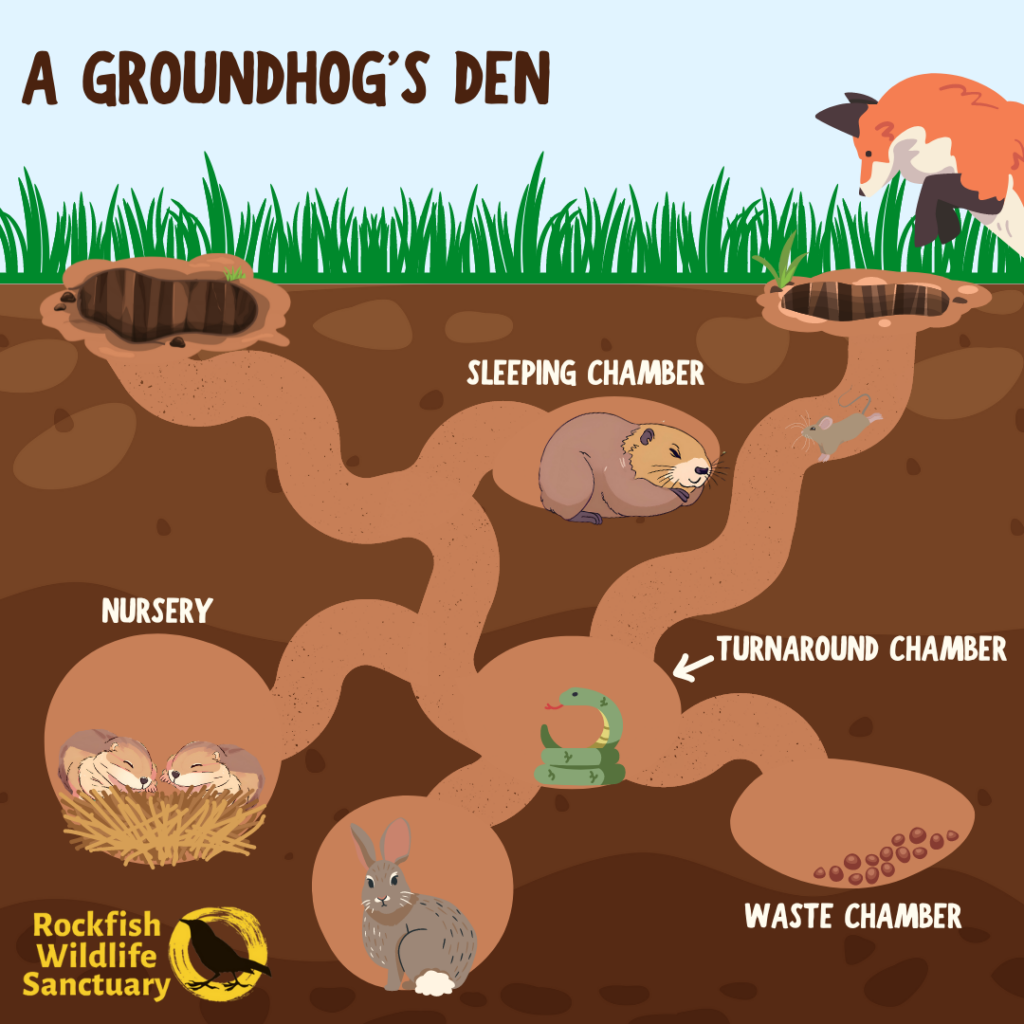

The groundhog’s burrow itself is charmingly complex and helps us understand these fascinating creatures a little more. They often build multiple entrances, allowing them to dive into their burrow to escape a predator and pop out the other side while the predator is still focused on the first entrance. Stretching up to 6 feet underground and up to 20 feet long, burrows have individual chambers for sleeping, baby rearing, using the “bathroom,” and even turning around. Yep, these rotund potatoes do need to occasionally build a space just to turn around in, as they’re too wide to do so in the connecting tunnels.

In a testament to their importance to other creatures, it’s even common for other species to seek refuge in a groundhog’s den. These include cottontails, mice, voles, shrews, skunks, lizards, and snakes. That’s right – groundhogs make great neighbors to their fellow fauna.

Believe it or not, groundhogs are important neighbors for humans too! Groundhogs move immense loads of soil as they dig, tilling and aerating the soil as they go. This creates a more suitable environment for the microbes that make our wild world go round, and it allows water to better permeate soil and replenish our ground supply. Similar to beavers, their larger rodent cousins, groundhogs can have an immense positive impact on the health of their habitats – including your backyard.

This does mean that groundhogs may vex folks who farm or garden. Groundhogs are mostly generalist herbivores, munching down on a wide variety of greens, including garden veggies if easily accessible. The most effective method to safely keep groundhogs away from your garden is to bury L-shaped hardwire fencing 1-2′ below ground or create a wide “sidewalk” around your garden so that groundhogs cannot dig themselves in next to the fence. Keep in mind that it is not legal to trap and relocate wildlife in Virginia, and licensed trappers must euthanize the animal once they leave your property. So, we advocate for coexistence!

In fact, if you’re someone that likes native plants, you’re someone that should like groundhogs. Okay, okay, we know we’re biased…but groundhogs really are essential to healthy plant ecosystems. They disperse native seeds, control native plants and invasive weeds, and even help pollinate flowers by getting pollen on their fur and inadvertently carrying it elsewhere while going about their groundhoggy business. (“Groundhoggy” is, of course, a very scientific term.)

Though they’re a common sight in lush prairies and forests this time of year, groundhogs are considered to be true hibernators when winter rolls around. They may dig a separate hibernating burrow, below the frost line, and hunker down when they’re at their very chunkiest in the late fall. A hibernating groundhog’s body temperature can drop to just 35 degrees, taking a breath every six minutes or so. 😮💨 We’ll admit we’re jealous. Can we hibernate next winter too, please?

A little behind the scenes knowledge as we close out this month’s Critter Corner: in rehabilitative care, groundhog patients tend to steal hearts not only because they’re absolutely adorable, but because they’re also quite “polite” as well. They are relatively quiet, they latrine in one neat spot in their enclosure, and they eagerly eat all of their greens. Of course, these behaviors reflect their natural history as a species and not a purposeful regard for our rehab team…but we certainly don’t mind. 😉

We love providing top-notch care to species like groundhogs, bats, skunks, and others who face poor reputations despite their incredible work for our backyards and beyond. We’ll always go hog wild for these animals!

May 28, 2024

Published:

Thanks for such a fun-filled article pro groundhogs. I actually gave up my gardening because I couldn’t keep them out of the fenced area, even burying the fence 1 foot down. and they climbed up and over the four feet it rose up, too. I have not tried laying fence out four feet as your photo indicates. Maybe I will try again, now that Trump had relaxed the restrictions on Forever chemical pesticides.

Thank you for reading, Janet! We’re glad to hear when folks are interested in non-lethal deterrents. Happy gardening!