August’s Patient of the Month was a surprising intake at the Sanctuary. Meet 24-836, an orphaned baby striped skunk! 🦨

Wildlife rehabilitation has trained us to expect the unexpected, and this kit and his six siblings were certainly unusual. Typically, we admit 20-30 orphaned striped skunk (Mephitis mephitis) kits each year, but they almost always come into care between April and early June. Yet here we are in August, thinking our few remaining skunk patients were almost ready for release – only to be surprised with with youngsters who had just barely opened their eyes. C’est la vie!

Unfortunately, 24-836’s rescue story is one we hear all too frequently with orphaned skunks, raccoons, opossums, and foxes: his mother was shot. A homeowner in Rockingham County shot the mother skunk, and when the babies stumbled out of their den in the following days, a kindhearted rescuer thankfully stepped in to save them. They were initially brought to our friends at the Wildlife Center of Virginia before being transferred to RWS shortly thereafter for long-term rehabilitation and release. We quickly got to work! We emulated their den-like environment by setting them up in our indoor nursery. We also weaned them onto specialized skunk formula, monitoring their fluids and digestion throughout. 🍼

Skunk rehabilitation does require a few extra safety considerations. No, we’re not referring to their smell! Skunks are considered a highest-risk rabies vector species in Virginia. This does not mean they have rabies, but rather, they are just at a higher risk for carrying compared to other species. In addition, skunks can occasionally carry diseases like parvovirus or distemper as well as internal zoonotic parasites that could make other patients (or humans) sick if inappropriately rehabilitated. All of this is to say: we maintain the highest standard of cleanliness and professionalism when working with this species. That’s reason #1,204,673 why wildlife rehabilitation should be left to licensed pros.

One helpful trick to maintain tidiness is to use small, empty cardboard boxes like this used glove box above as a nursery hidey-hole! After a day of use (including lots of smushed food), we can safely discard the old box and provide the kits with a new one, giving extra life to a box that might have otherwise just been tossed. In addition to wearing full PPE when we work with these patients, “recycling” materials like this is important when it comes to preventing cross-contamination between patient groups or exposure to staff.

To address the whole “stink” thing: yes, skunks in care at RWS do smell. While even infant skunks do have an unmistakably musky eau de Mephitis about them, avoiding their full-blown defensive spray is easy. Skunks stomp to warn you that you are too close. When our rehabbers see that behavior in the course of tending to them, we give them their space. When we need to pick up skunk patients for a wellness exam or medical treatment, we simply tuck their tail under their stomachs to prevent them from spraying their iconically pungent perfume. And, that’s reason #1,204,674 why you shouldn’t try this at home. (It’s illegal and stinky. Lose-lose.)

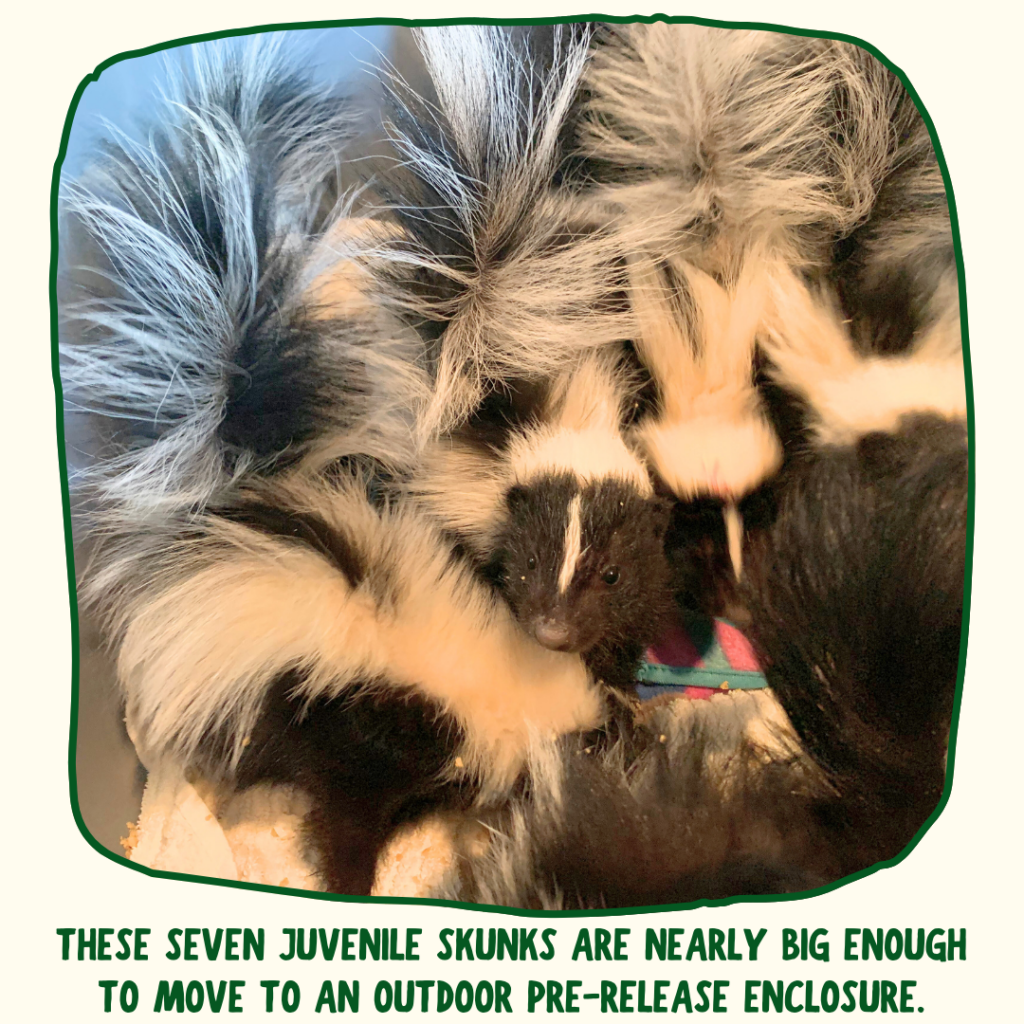

24-836 and his siblings are almost ready to “graduate” to one of our outdoor pre-release enclosures, right after the current occupants get released back to the wild. They’ve proven their ability to head outdoors not just in their impressive defensive posturing, but also in their incredible capacity to eat! These kits have been self-feeding entirely for over a week now and are transitioning onto “adult meals” where the food is not softened in advance. Soon, they’ll be introduced to a skunk patient’s favorite menu item at RWS: live mealworms and grubs. 🪱 In the meantime, enjoy this video we took just this morning of 24-836 and his siblings showing off their impressive eating skills.

There is a small chance these seven stinkers will become long-haulers, compared to the orphaned skunks we receive earlier in the season. Striped skunks typically stay with their mother for five to six months, so this may necessitate keeping this litter over the winter if they are not developed enough to be fully independent by the time temperatures drop. In fact, we usually have a small handful of late-blooming patients that spend the winter at the Sanctuary.

If we do need to overwinter 24-836 and his six charming siblings, rest assured they will receive the best possible care until spring brings their long-awaited, much-deserved release. ❤️🎉

August 15, 2024

Published:

Be the first to comment!