For many of us northern hemisphere humans, January means snow. ☃️

Mother Nature certainly didn’t disappoint this week in Virginia, with potentially more on the way this weekend! ❄️

While you’re staying toasty on the couch or perhaps shoveling your driveway (we salute you 🫡), our wild neighbors are adapting to winter. However, we tend to hear the most about wild animals that get the heck out of Dodge (migrate) or get the heck…under Dodge (hiberate). What about the many species that don’t do either?

To kick off 2025’s educational Critter Corner newsletters, we’re highlighting the critters that actively keep us company throughout the coldest months and how they do it…without blankets, hot cocoa, and Netflix. Crazy, right?!

For starters, not all birds migrate! Some species, like Blue Jays, Northern Cardinals, and Carolina Wrens, have resident populations, meaning these individuals stay put year round. That’s because our winters tend to be relatively mild – a fact that is perhaps debatable for some of the humans reading this. 😆🥶 It’s still cold, of course, so resident birds have a few ways to keep warm. Tactics include:

- Fluffing up: Poofed feathers create insulation and make our neighborhood birds look charmingly rotund.

- Shivering: Like humans, shivering helps these warm-blooded animals generate heat.

- Co-roosting: Some species huddle together in vegetation, tree hollows, or nest boxes to share warmth, especially on bitterly cold nights.

Believe it or not, some birds actually fly to Virginia as their winter destination. For example, you might notice flocks of small, dark sparrows flitting around if you go for a drive. These are likely Dark-eyed Juncos, and they spend summer in the arctic and winter in more temperate regions. Come springtime, save for some residents, these peppy birds will head back north to breed.

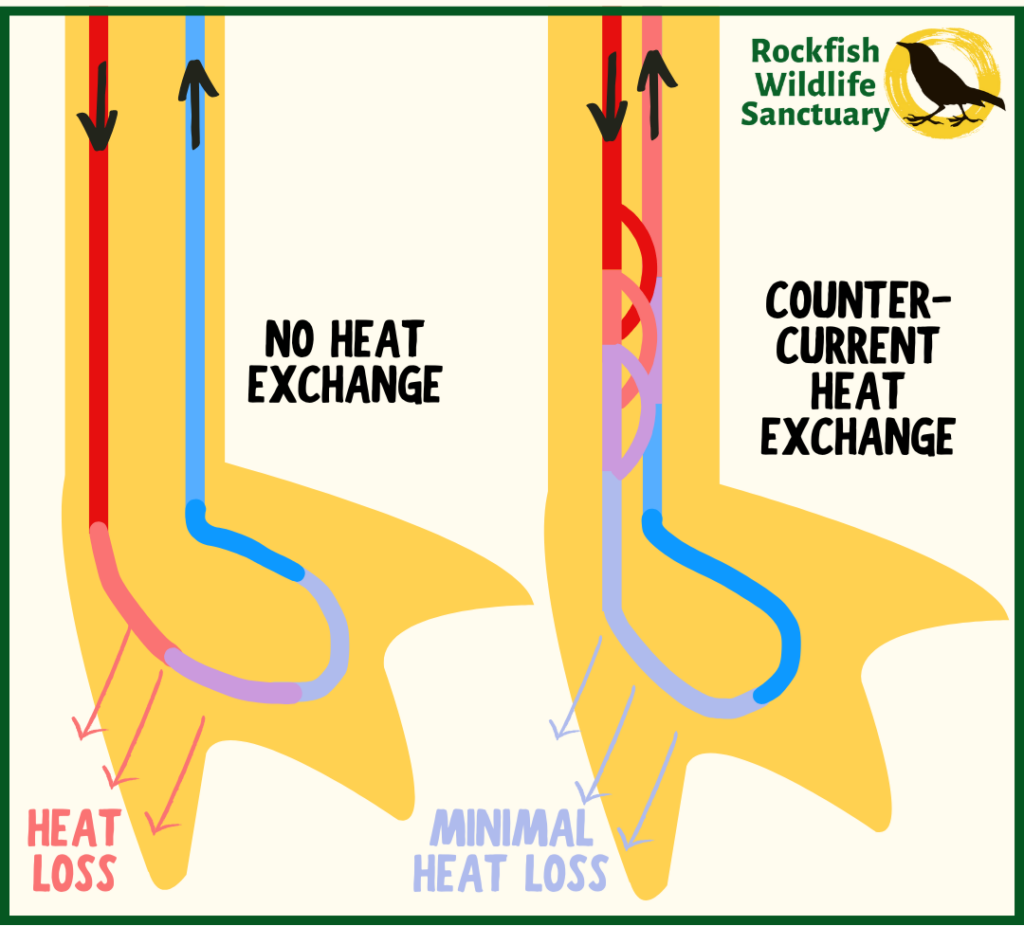

What about birds that swim in the winter? How do native waterfowl survive such frigid water? 🦆👙 Ducks and geese have a fascinating structural adaptation in their legs that allows for countercurrent heat exchange. Blood vessels in their legs are arranged closely together, so warm blood flowing from the body passes closely alongside cooler blood returning from the feet. This setup transfers heat to the cooler blood, keeping the warmth in their core and preventing excessive heat loss through their feet – even when they stand on icy surfaces or float in freezing water. It’s a built-in energy saver! Marine mammals, like seals and whales, also use countercurrent heat exchange to keep warm.

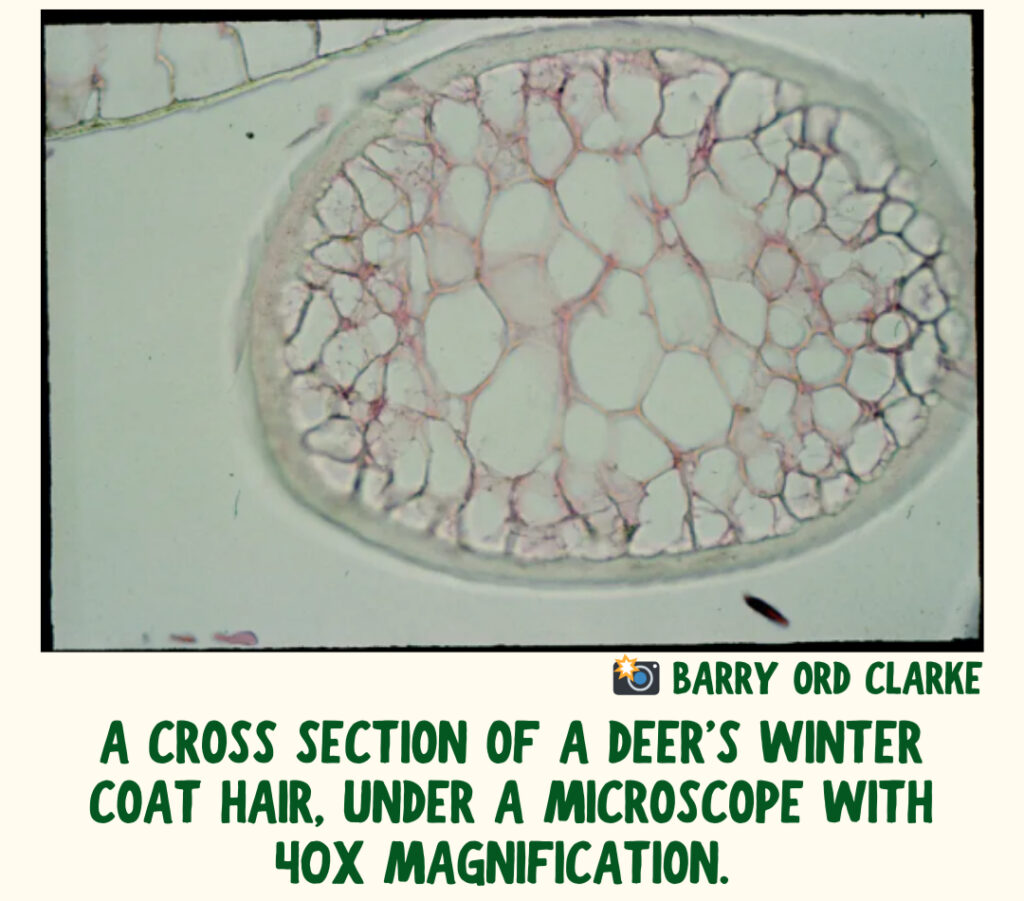

Speaking of mammals, there are quite a few mammal species in Virginia that brave the winter rather than hibernate or migrate. 🦌 Take deer, for example. Deer coats don’t look that warm and fluffy from afar, but they’re hiding a unique superpower: hollow hair. These outer hairs are not hollow like a straw but rather contain a lattice of tightly packed cellular air pockets, creating an extra layer of protective insulation for the deer’s undercoat and skin.

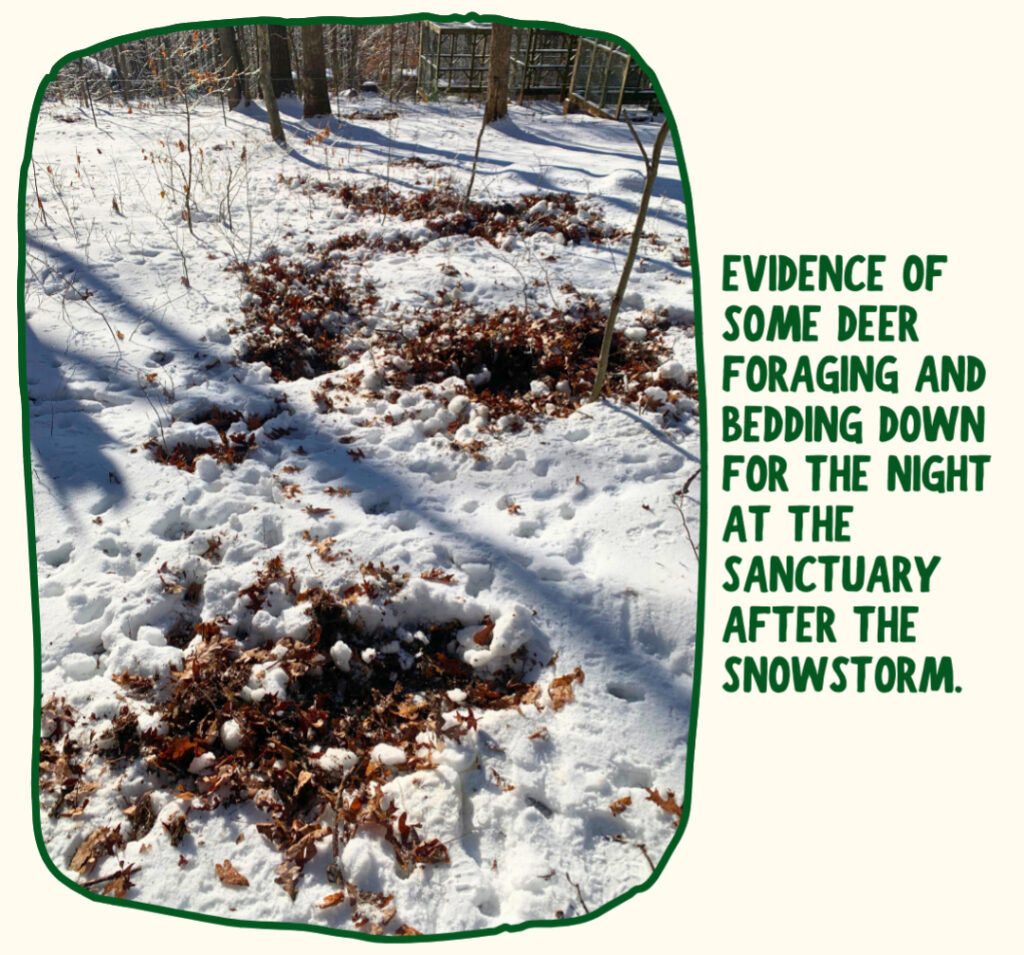

White-tailed Deer also adapt to the season by shifting their diet to twigs, bark, and other woody plants. If you come across swaths of upturned snow in the woods, it’s likely from deer foraging in the leafy layer beneath or making a nice spot to sleep in. We found a few “deer beds” at the Sanctuary this week. ⬇️

Squirrels are perhaps the most famous of our wild neighbors when it comes to winter prep. 🌰 Rather than hibernating, they spend the fall packing on the pounds (okay, ounces) and storing thousands of nuts in different hiding spots, called caches. Contrary to popular belief, squirrels actually remember their caching locations quite well and create a mental map to do so. Their strong spatial memory is connected to the hippocampus, the part of our brain that’s essential for learning and storing information. Scientists have found that squirrels have a larger hippocampus than similar species that do not cache food! 🧠

On the other hand, species like Red Foxes often change up their diet to get through wintertime. 🦊 Foxes typically rely heavily on scavenging in the winter, with one European study finding that fox diets consist of up to 44% ungulate carrion in the coldest months. This is a big difference from their summer diet, where they largely feast on berries and insects. Foxes may hunt birds more actively and other non-hibernating small game, like cottontails or mice, in winter.

Last but not least, there are the true warriors: mammals that don’t store food or build up much fat ahead of winter and simply must survive. 🦝 Raccoons can go into torpor, a state of lowered metabolism, and spend time hiding out in tree hollows. On milder days, they’ll forage for anything they can find. Skunks behave similarly but often den together to keep warm. Some might pack in a dozen others to share the heat! However, scientists have found that fewer resources to go around can lead to about 50% mortality among skunk populations. Luckily, breeding season for these animals kicks off in February when love (and stink!) will be in the air again. 🦨❤️🦨

Opossums have perhaps the toughest go of things. 😅 They do not den communally and their bare fingers, ears, and tails make them particularly vulnerable to frostbite. You won’t find these creatures in the Rocky Mountains, but they typically manage just fine here in Virginia by bedding down in grass-lined dens during our coldest days. It’s no wonder these marvelous marsupials live just a year or two. Nonetheless, they’re doing pretty darn well as a species. They’ve remained relatively unchanged since the age of the dinosaurs! 🦖

At the Sanctuary, though, our opossums have a much cushier winter experience. Our education ambassador opossums have the luxury of staying indoors when it drops below freezing. They don’t know how good they have it. 🤣

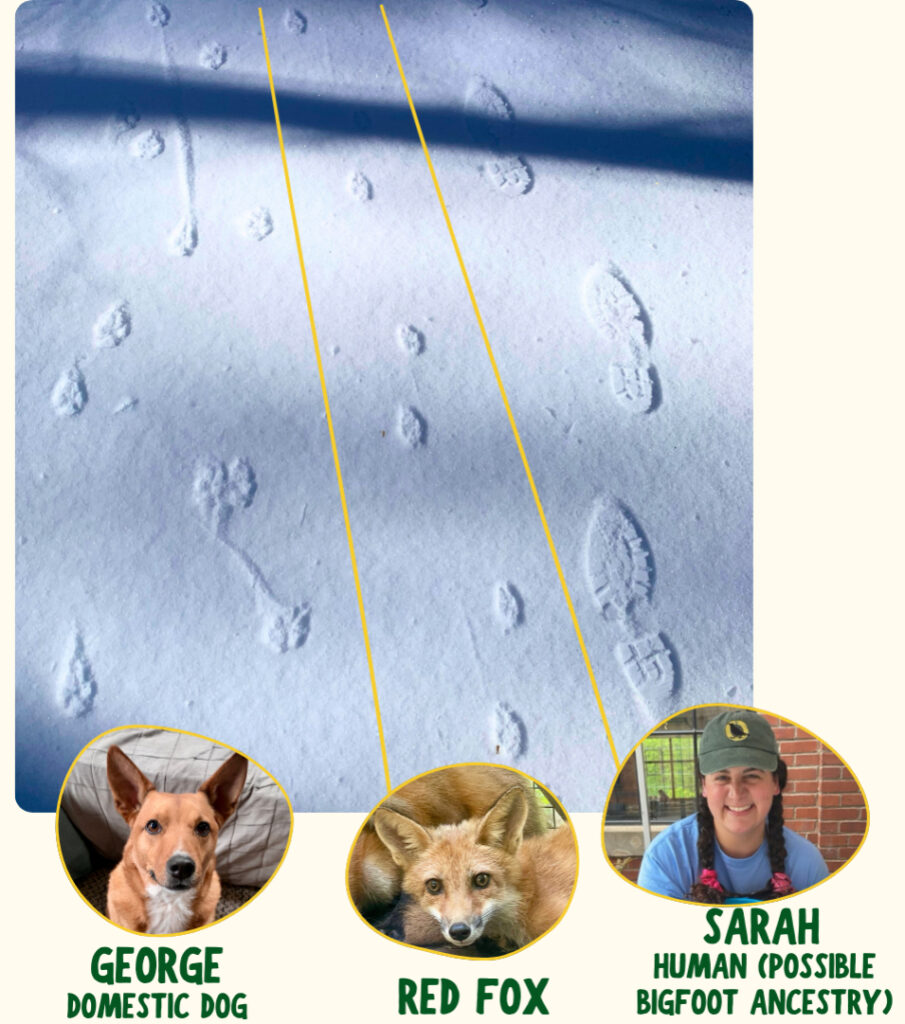

We had fun tracking deer, squirrels, and foxes across the Sanctuary property this week thanks to lots of snowy footprints. 🐾

We even found a fox den by following a determined set of prints. 🦊 Our director, Sarah, snapped the picture below comparing the footprints of her 45 lb dog to a red fox’s. Note the narrow, methodical gait of the fox and the delicate size of each print. If you’ve found any interesting snow prints, tag us on social media so we can see what other critters are up to in our community!

We hope you enjoyed learning a little more about how local wildlife gets through the winter. At the very least, you’ll probably appreciate that blanket and cocoa more now! 😄☕️

Please stay safe in this winter weather, and thanks for reading this month’s Critter Corner. ❄️

January 10, 2025

Published:

Be the first to comment!