As birds flit to and from their nests, fox kits dash around their dens, and humans call the RWS hotline all day long, one species is taking things slow…very slow. Cumbersomely slow, in fact.

We’re talking, of course, about the charming Common Snapping Turtle!

We have received so many calls about these dinosaurs turtles this spring. Last week, in fact, a concerned person called saying they’d just seen a snapping turtle get hit by a car in Crozet. They wanted to know how to help and were heading home to grab a container for it.

Immediately after they hung up, we had another call come in about that very same turtle! Two other Good Samaritans had already stopped to contain the turtle and get him help. It warmed our hearts to know that so many people cared about this animal—and yet, many others feel scared of them or simply don’t know that help is an option.

This month, we wanted to highlight the Common Snapping Turtle (Chelydra serpentina) to help arm folks with the knowledge they need to identify a snapper in trouble and to safely assist that turtle. With your help, we can get more folks to appreciate and, dare we say, even admire these oft-maligned yet important animals.

Prehistoric Origins

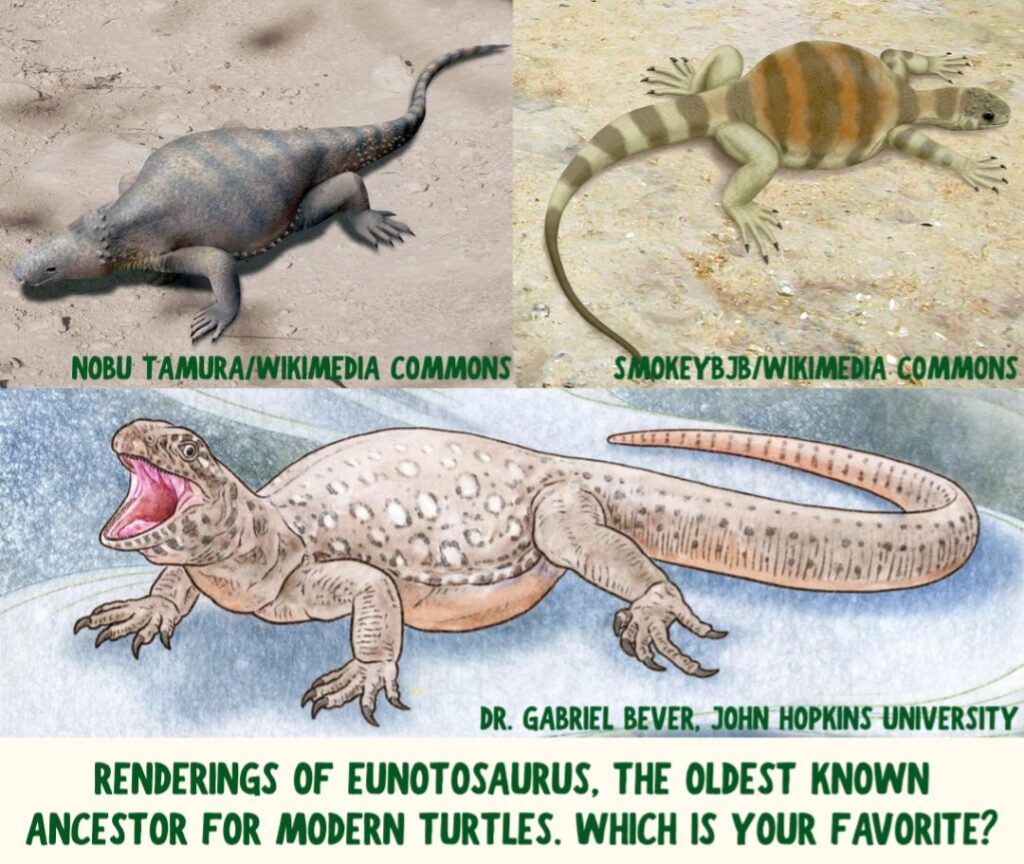

It turns out that we weren’t that far off when we joked about snappers being dinosaurs! The oldest known suspected ancestor of modern turtles is Eunotosaurus, a funny-looking lizard whose small head and wide body laid the evolutionary groundwork of the modern turtle shell. These creatures lived 260 million years ago in the Permian period—before the age of the dinosaurs, which began around 245 million years ago.

The snapping turtle family itself is ancient, too. Chelydridae evolved roughly 90 million years ago here in North America and is considered to be the ancestral lineage for 80% of modern turtle species. Ted Levin’s lovely piece in Audubon Magazine described the snapper’s staying power beautifully:

“Snapping turtles have witnessed the drift of continents, the birth of islands, the drowning of coastlines, the rise and fall of mountain ranges, the spread of prairies and deserts, the comings and goings of glaciers.”

With their prehistoric appearance, Common Snapping Turtles today tend to spark more fear than admiration. But fear not: they are not the aggressive, finger-chomping monsters they’re often made out to be.

One big snapping family!

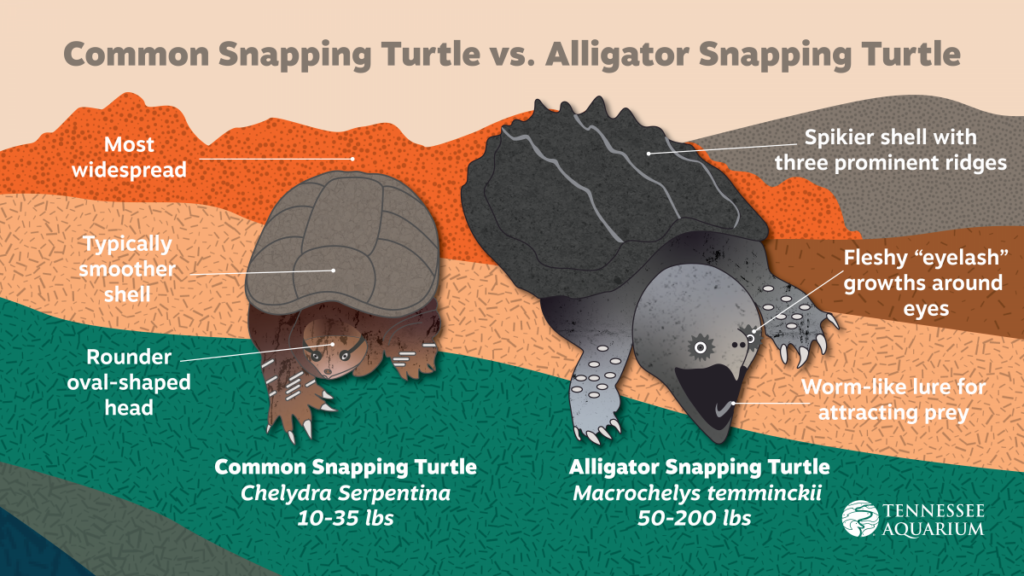

The Common Snapping Turtle is Virginia’s largest native freshwater turtle and one of the largest turtle species in North America. The average adult’s carapace (upper shell) measures about 10-14 inches, and they weigh in usually between 10–35 pounds. However, the heaviest wild-caught snapper specimen topped out at 75 pounds!

A quick note that our native Common Snapping Turtle is different than the larger Alligator Snapping Turtle. This graphic from the Tennessee Aquarium does a great job highlighting their differences. ⬇️

The Alligator Snapping Turtle is native to the southeast’s Gulf Coast drainage area and the Mississippi River Valley. It has occasionally been spotted in Virginia, but these rare instances are most likely due to captive-bred alligator snappers being dumped illegally. 😞 You will not encounter these giant turtles in our waterways, though we do think they have a certain charm about them!

Snapping Turtle Benefits & Myths

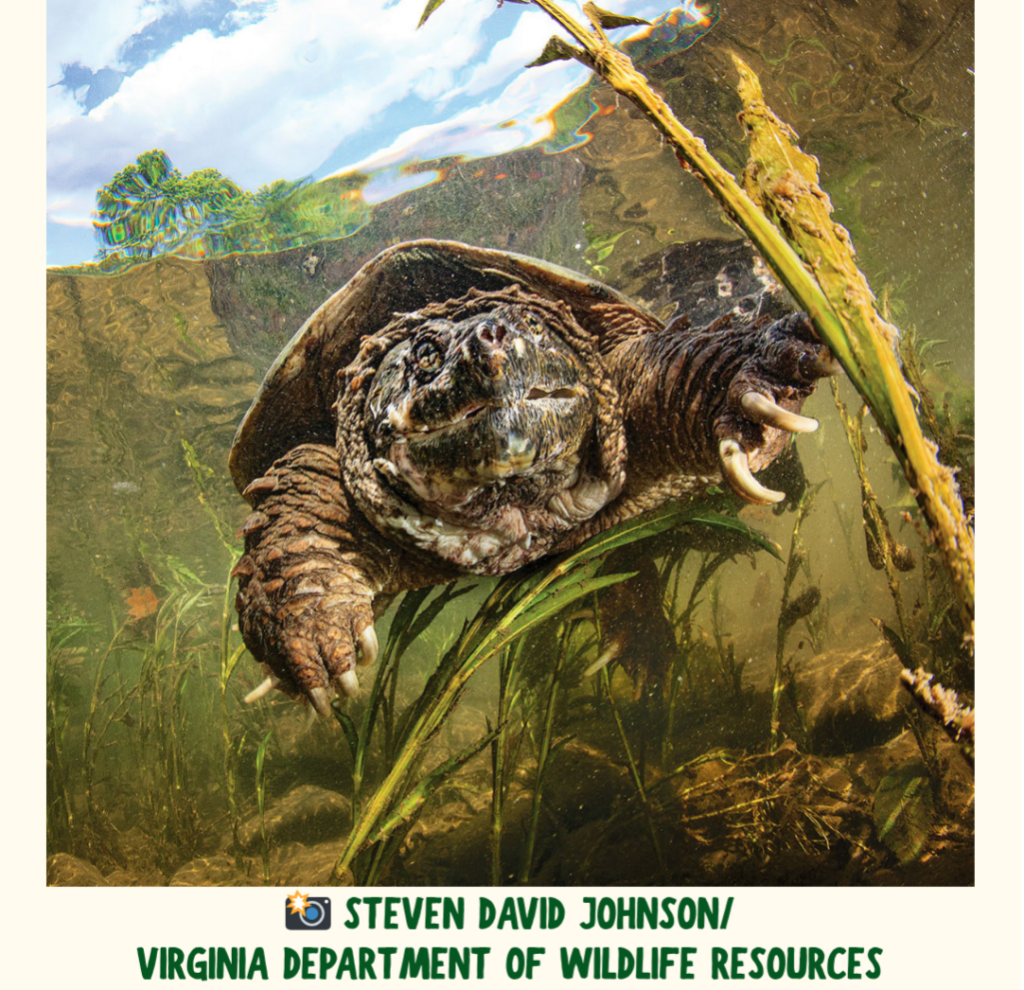

Now back to the star of the show. Common Snapping Turtles live in a variety of aquatic ecosystems, including rivers, ponds, lakes, brackish waterways, and the occasional big, muddy ditch. 🤣 Snappers spend most of their lives underwater, rarely basking the way other freshwater species do throughout the summer.

After taking a breath, they can stay underwater for 30–40 minutes to gobble up all sorts of goodies! Snapping turtles are largely scavengers. They readily eat insects, frogs, fish, aquatic plants, small birds and mammals, smaller turtles, and tons of carrion (dead animals). By eating dead and decaying things, they keep freshwater ecosystems clean. This helps prevent disease spread and recycles nutrients back into their surroundings. Thank you, snapping turtles!

The snapping turtle’s reputation inaccurately precedes it when it comes to that bite. They lack teeth, instead relying on their sharp beak and strong jaws to munch on a variety of foods. Though being bitten by a snapping turtle would certainly hurt, they cannot sever a finger or break through a broomstick in one bite—two myths we hear a lot.

In reality, a human’s bite force is much stronger than a snapper’s!

Do they really snap?

Snapping turtles are truly quite shy. They are ambush predators underwater, and they have no interest in biting toes that are clearly attached to a giant, fleshy monster (humans)—nor are they interested in chasing you down to do so. Instead, these elusive turtles laze around and wait for small prey to float by or use their well-developed olfactory bulbs to follow the scent of a delicious rotting carcass. 👃

Their reputation for aggression has been misinformed by their behavior on land, where they are quite literally out of their element. Snapping turtles occasionally lumber out of the water to forage, search for mates, or lay eggs. Without their speedy swimming skills, they can no longer quickly evade predators. Further, they are not able to tuck their head or limbs into their shells like other native turtles can. Without that ability to hide, their only option to defend themselves when scared is to bite! Leave snapping turtles alone and they will gladly return the favor. ☮️

The only time you should not leave a snapping turtle alone is when it is crossing the road. They need to be helped across just like box turtles do! Do not pick them up the way you would a box turtle, though. Instead, hold the snapper from the back and scoot him across. The North Carolina Zoo has a wonderful video describing this process. Check it out below! ⬇️

If you encounter a Common Snapping Turtle that has been hit by a car, contain the turtle in a box, note exactly where it was found, and call RWS or your nearest licensed rehabber immediately. Turtles experience pain and suffer like any other animal and deserve professional help.

When & How to Help Snapping Turtles

Other than folks calling to ask how they can help a snapper cross the road, there are two other common calls we receive on our wildlife hotline about snapping turtles.

☎️ “I found a teeny orphaned snapping turtle! Can RWS care for him?”

Nope, you didn’t! Like most reptiles, hatchlings receive no parental care. In fact, they likely will never even meet their parents. If you have found a hatchling snapping turtle, you do not need to intervene unless the turtle is in immediate danger from unnatural causes. 🙅 We make that specification because predation from native animals is normal, and we do not condone intervening in those interactions. However, if the hatchling turtle is on a sidewalk, crossing a road, or being followed by an outdoor cat, please help the turtle cross the obstacle or get to a safe place within a few feet. You do not need to put it into water or move it to water. Snappers know where they’re going, from birth!

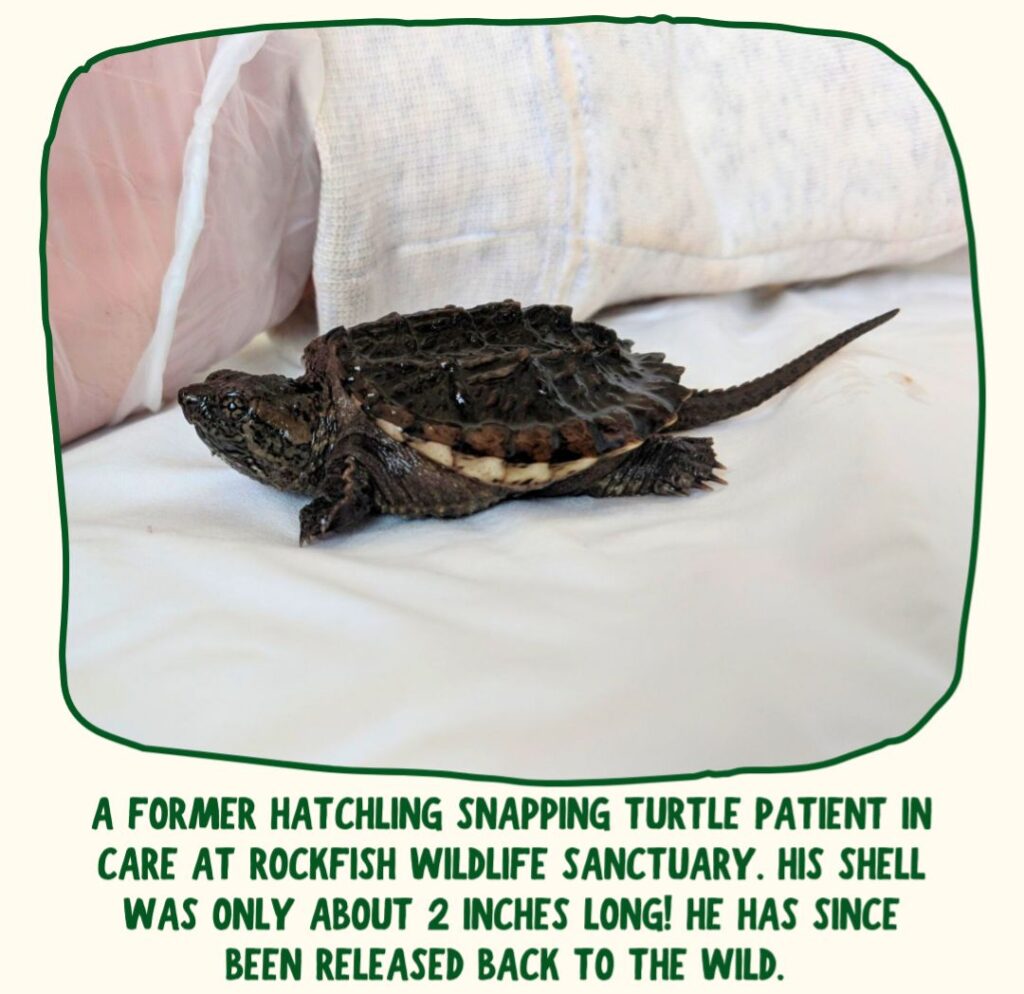

Because Rockfish Wildlife Sanctuary specializes in caring for clinically healthy orphaned wildlife, we do not often admit snapping turtles. That said, we do typically admit at least one kidnapped snapper or a briefly-kept illegal pet snapper every year. These individuals are often able to be rehabilitated and released back to the wild, like this particularly memorable patient from last year. ⬇️

☎️ “There’s a giant turtle in my yard, and I don’t live near water?!”

In almost every case, this is normal. Come late spring, female snapping turtles trudge out of their aquatic habitats and waddle around in search of the perfect nesting spot. Females may travel up to ten miles away from their watery home before selecting some sandy soil (or even some fresh topsoil in your garden) to lay eggs in. She spends a few moments digging a hole with her back legs before laying about 20-60 eggs over the next few hours. Then, mom leaves! You likely won’t see her again, unless she chooses to come back next year. 👋

So, if you see a snapper in your garden, leave her be while she does her job. If you can, try to avoid that area in your garden—some folks use flags to mark nests to remind themselves. 🥚

Don’t assume you’ll suddenly have 60 baby snapping turtles in your yard one morning, though! Only about 5% of eggs will actually hatch, since nests are readily preyed upon by animals like foxes, raccoons, snakes, and opossums. After 80-90 days, any lucky remaining eggs will hatch, and the tiny snappers will immediately disperse. Typically, only about 1% of baby snappers survive the 10–16 years needed to reach reproductive age.

Snapping turtles…for dinner?

Snapping turtles who do survive their treacherous youth typically enjoy long, healthy lives. They may live upwards of 50 years! Sadly, though, humans pose an increasing danger to snapping turtles through car collisions and over-harvesting. ☹️

You might be surprised to learn that the Common Snapping Turtle is a game species in Virginia. These turtles were unfortunately facing steep decline in the early 2010s due to relatively unregulated harvesting. In fact, the 2013 harvest represented a 1,300% increase from the 2002 harvest. At the time, roughly 70% of the harvest was attributed to out-of-state individuals who were taking turtles largely for exporting their meat abroad as food.

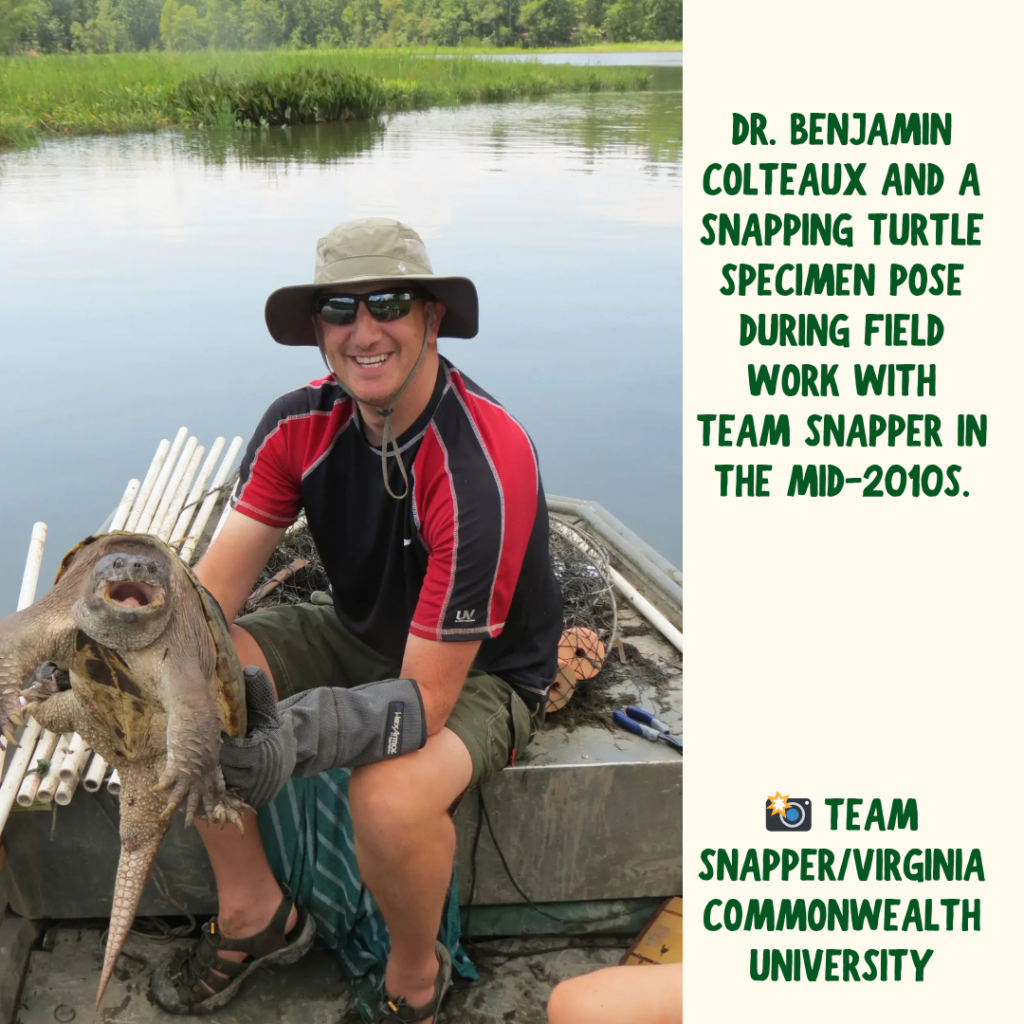

As you might imagine, rampant harvesting has had a big impact on turtle populations. Virginia Commonwealth University’s “Team Snapper” researchers found that Totuskey Creek, located off the Rappahannock River, experienced annual harvest rates of nearly 50% of the local snapping turtle population from 2012–2015! Meanwhile, they found that snapping turtle populations increased by 4% in an area where no harvests were happening.

The resulting study from Team Snapper, led by Dr. Benjamin Colteaux, was instrumental in getting new state regulations passed in 2019. Virginia capped the number of permits issued annually, limited permits to in-state residents only, and increased the minimum curved carapace length of harvest-eligible snapping turtles from 11 inches to 13 inches in order to reduce the number of young individuals taken. These regulations will hopefully reduce pressure on these slow-growing turtles and allow populations to recover more.

Let Team Snapper’s work be an important reminder that science and policy can work together to protect even the most often-overlooked species. When research informs action—and when concerned citizens, biologists, and lawmakers unite—real change is possible.

⬆️ Some more precious hatchling snapper shots from our friends Jeff Morgan and Erin Bishop of Charlottesville’s Chime Studio.

With your continued awareness and compassion, we can give snapping turtles the space and respect they need to thrive for another hundred million years. 🐢✨

Thank you for reading this month’s Critter Corner! Now if you’ll excuse us, we’ve currently got 191 wildlife patients to feed. Happy baby season! 🍼

May 30, 2025

Published:

I work at Home Depot and one day

I seen hatchling snapper walking around in the store.

So I took it home and I’m taking care of it until it’s old enough to be released I understand I’m not supposed to take them in but I do plan on releasing it eventually

Please contact your nearest wildlife rehabilitation organization. Snapping turtles have extremely specific care requirements in any captive environment, and a wildlife rehabber will need to assess the turtle’s ability to return to the wild using their skillset and a medical exam. Feel free to contact us via email and we can help you find a rehabber close to you!