Well, summer has certainly arrived in full force! 🥵

This week’s heat wave has our team savoring every possible moment inside our air-conditioned building and enjoying a steady flow of popsicles. 🧊

We keep things cool for our outdoor pre-release patients at RWS by providing shade, plenty of cool water, and even frozen enrichment items, like fruit and mealworm popsicles made inside of ice molds. 🪱 To clarify: the popsicles our human staffers are eating do not contain mealworms.

Our ambassadors have also been getting treated to some occasional cool mist from our hose to cool down. Jack the Red-tailed Hawk particularly enjoyed that today! ⬇️

But how do wild animals stay safe in extreme heat, especially if they aren’t getting mealworm popsicles delivered to them daily?

We wrote back in January about how local wildlife survives the winter, so it seems fitting given the soaring temperatures that we should share a bit about how our wild neighbors survive our hottest, swampiest days. They do it without watching Netflix in the A/C or heading to the ice maker for another handful, if you can believe it. 😲 And in even cooler news?* You can help your wild neighbors get through these extreme conditions with a few quick tricks!

*See what we did there? Heh. 😎

For starters, many species use evaporative cooling techniques. This process looks different between species, but we’ll start with the basics. Think about how it feels to go for a swim on a hot day. As you step out of the water, you might feel a chill as your wet skin hits the air. That’s evaporative cooling! Evaporating water into vapor takes energy (heat). As water evaporates off your skin, it dissipates some of your body heat and leaves you feeling cooler.

As humans, sweating is our main method of evaporative cooling. It’s an adaptation we are lucky to have evolved as endurance predators…though sweating certainly might not feel like a privilege this week when your typically pleasant walk to work has you completely drenched before your 9AM meeting. 😅

Now that we’ve covered the science behind evaporative cooling, let’s dive into how wild animals put this principle and a few other heat-busting strategies to good use.

The animals you’ll most likely see cooling off are birds, since most of us encounter at least one bird every single day of our lives…even if it’s through your office window. Our feathered neighbors have a few tricks up their sleeves wings to beat the heat. ⬇️

Hiding out:

On hot days, birds are apt to stay still in the shade of a tree or dense vegetation. If your yard seems a bit quieter, it’s because your avian neighbors are also trying to be as lazy as possible to get through the day.

Panting & gular fluttering:

Much like a dog, panting increases evaporative cooling from a bird’s mouth and throat. Many bird species take this a step further by fluttering their gular region (throat) muscles. By rapidly vibrating these muscles and their hyoid bone, they increase cooling throughout their respiratory tract. Hot blood rushes toward this region, and the air moving across the moist throat membranes helps wick that heat away. Here’s a great example of gular fluttering, featuring some adorable Great Horned Owlets. 🦉👇

Spreading wings & fluffing feathers:

It’s not uncommon to see birds stretching their wings out on a hot day. Not only does this allow cool air to flow through their feathers, but it can also help kill parasites like feather lice by blasting them with UV rays and making it easier for a bird to see and preen them away. In this same vein, birds might also ruffle and fluff out their feathers on a hot day, releasing hot air trapped below and allowing cooler air to move across their skin. 🪶

Pooping on themselves:

Yes, you read that correctly! Our native Black Vultures and Turkey Vultures are real pros at keeping cool. They defecate on their own scaly, naked legs, which results in evaporative cooling through a process called urohydrosis. 🚽 An added bonus is that their urine is extremely acidic, and relieving themselves in this manner can kill bacteria that have gotten stuck on their legs after a day of stomping around in carrion. We love seeing our ambassador Black Vulture, Rosie, showing off his natural urohydrosis skills on a hot day.

Bathing:

Though most birds aren’t cool enough to bathe in their own pee like vultures are, taking baths is an important tactic for birds of all species and sizes to keep cool! Bathing is a behavioral instinct that many birds are born with. It’s always a joy to see fledgling patients at RWS start to show off this behavior, like this Red-bellied Woodpecker fledgling in our flight enclosure this past weekend!

Providing a bird bath can be a lifesaver during the dog days of summer, but only if it’s done safely. Here are some essential and easy tips for keeping your feathered friends happy and hydrated:

- Pick a shady spot for your bird bath to keep water temps cool and prevent algae growth. 🌳

- Check your water every couple hours on hot days to make sure it’s not scalding! Better yet, opt for a bird bath with a bubbler to help refresh and cool it down. 🥵

- Ensure the bath is no deeper than 2 inches maximum, and it’s best if it has gently sloping sides. 💧

- Add a clean rock or stick to the bath to provide perching surfaces for the birds to safely stand on while drinking or bathing. 🪨

- Put the bath at least 10 feet away from any bird feeders or food sources to prevent droppings or seeds from contaminating the water. 📏

- Clean your bird bath 𝗮𝘁 𝙡𝙚𝙖𝙨𝙩 once per week with soap and water, followed by a 10% bleach solution that you let the bath soak in for 10 minutes before rinsing with water. 𝘐𝘧 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘤𝘢𝘯𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘤𝘰𝘮𝘮𝘪𝘵 𝘵𝘰 𝘤𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘯𝘪𝘯𝘨 𝘺𝘰𝘶𝘳 𝘣𝘪𝘳𝘥 𝘣𝘢𝘵𝘩 𝙖𝙩 𝙡𝙚𝙖𝙨𝙩 𝘰𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘱𝘦𝘳 𝘸𝘦𝘦𝘬, 𝘥𝘰 𝘯𝘰𝘵 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘷𝘪𝘥𝘦 𝘢 𝘣𝘪𝘳𝘥 𝘣𝘢𝘵𝘩. 🧼

Of course, birds aren’t the only ones feeling the heat. For Virginia’s reptiles and amphibians—who rely on external temperatures to regulate their body heat—summer weather can be both a blessing and a serious challenge. When the sun’s blazing, these cold-blooded critters have to get creative to avoid overheating.

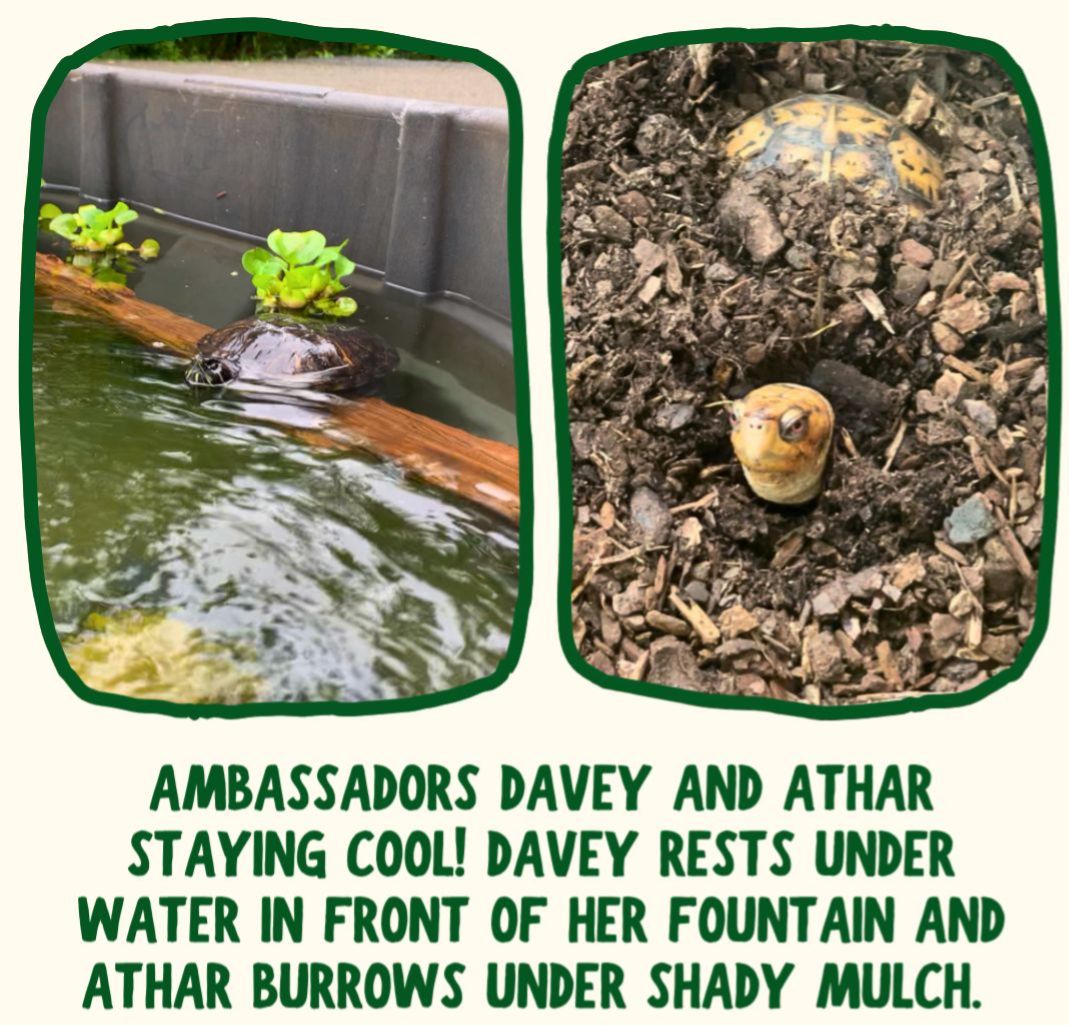

Box Turtles and snakes are pros at this. On sweltering days, they’ll bury themselves in loose soil, leaf litter, or even under a rock to escape the sun’s rays. If they’re lucky enough to find a puddle or creek, they might take a quick dip to cool down just like we do. Remember, though, that box turtles do not actually swim—and neither do most snake species. Never throw a terrestrial animal into water. In fact, don’t even pick ’em up unless you’re simply helping them cross the road. 🚗

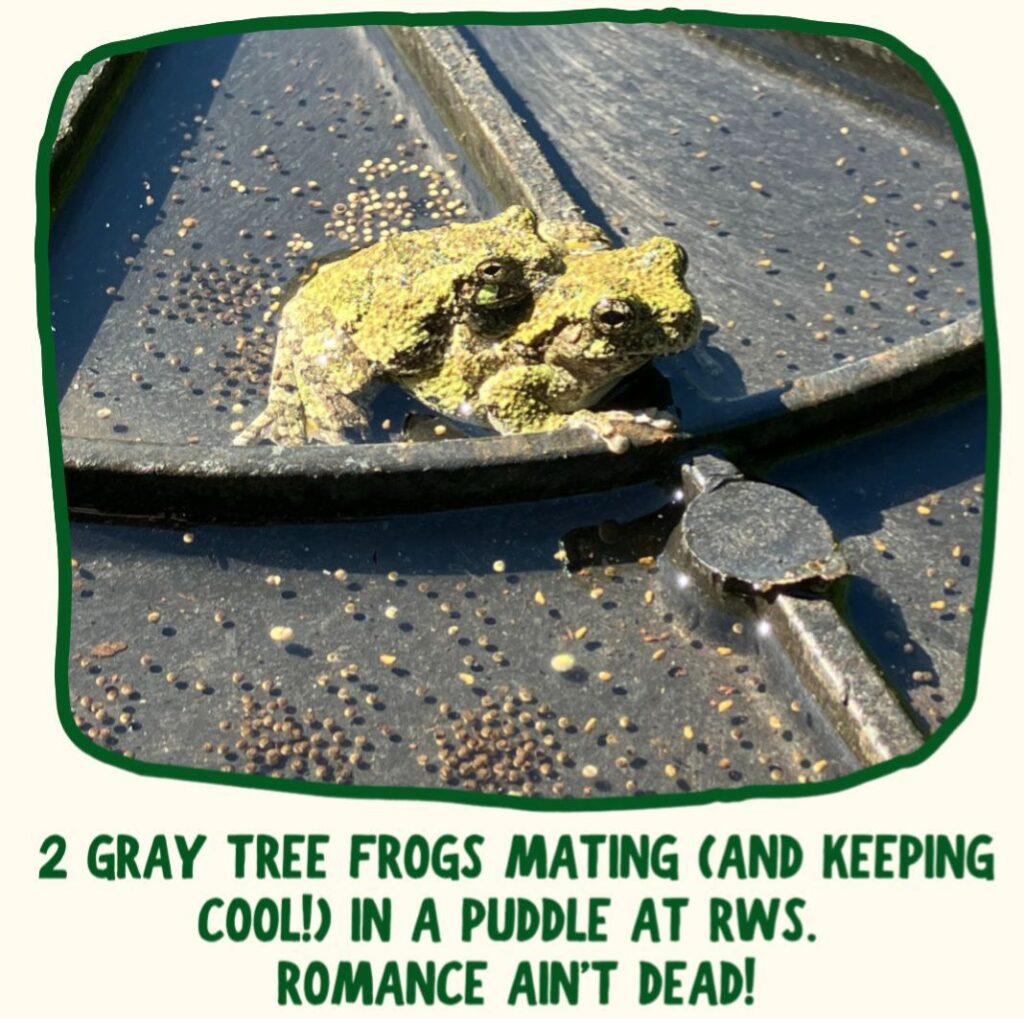

Amphibians, too, are at the mercy of their environment. Frogs, toads, and salamanders must stay moist so their skin can facilitate gas exchange and help them breathe. Many will spend the hottest summer daytime hours hidden away in damp crevices or burrows, emerging only at night when it’s cooler.

If conditions get extreme, some amphibians enter a state called estivation. This process is a sort of hot-weather hibernation, where they burrow down and lower their metabolic rate in an effort to reduce moisture loss. Other amphibians, like some salamander species, will instead make a moist cocoon to survive potentially desiccating conditions. What do they make their cocoon from? Their own old shed skin cells, of course! Charming. 😆🦎

What about our mammalian neighbors? How are they coping without ice cream?! Unlike herptiles, mammals are endothermic (warm-blooded). This means they produce their own body heat. Considering most species don’t sweat like us, native mammals stay cool using a combination of physical adaptations and behavioral shifts.

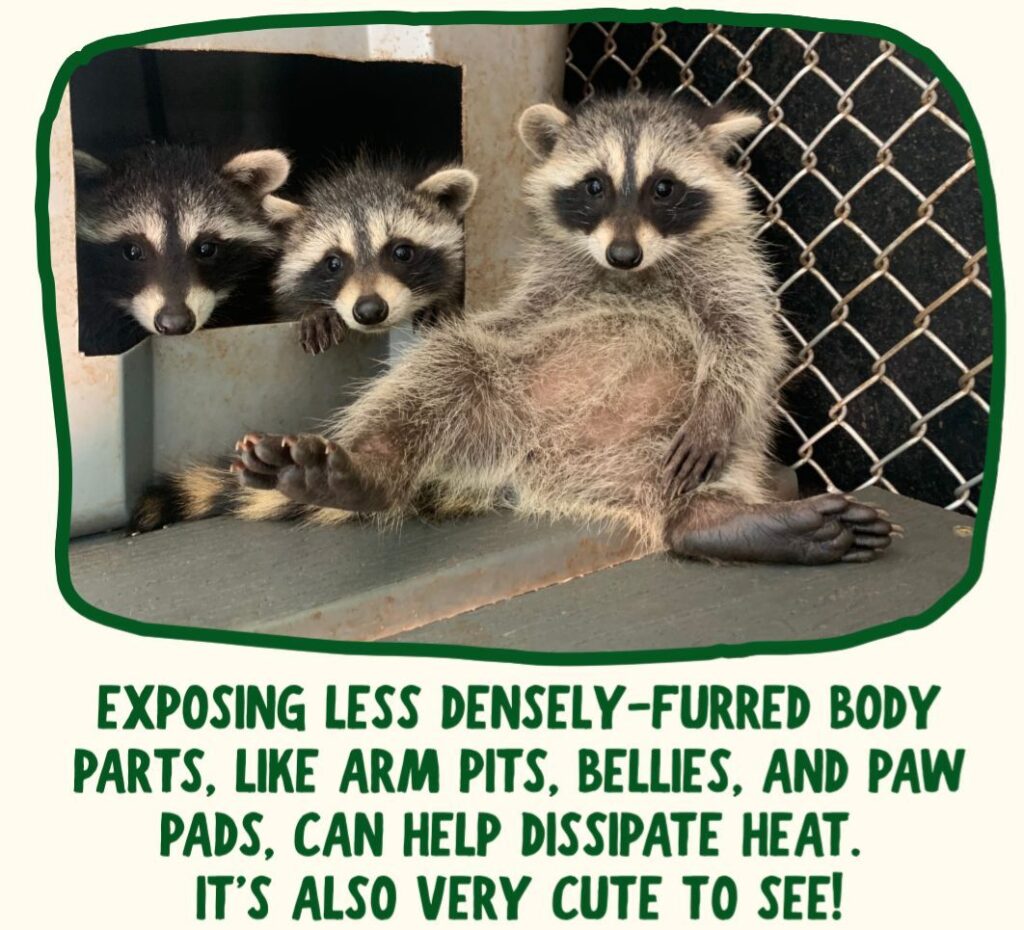

For starters, many furred species shed their underwear! 🩲 Well, kind of. Species like American Black Bears shed much of their soft, downy undercoat and even some coarse guard hairs. Doing so allows fresh air to hit their skin and prevent warm air from getting trapped. Though they can’t sweat, many native mammals can release heat through their paw pads or the less-furry skin under their limbs. Rolling onto their backs to expose that skin to the breeze or wading into cool water helps maximize the effect.

Large, thin ears also help some native mammal species cool off. Deer and Eastern Cottontails are lucky to have big ears, which help them sense potential predators nearby and assist with thermoregulation. That’s because air passing along the surface of their large ears cools blood down before it heads back to the animal’s heart, preventing their core body temperature from rising too much on a hot day.

Ultimately, many native mammals simply beat the heat by exhibiting what we like to call “strategic laziness”—our new favorite phrase. (“Sorry, can’t go for a jog today. I am being strategically lazy.”) Mammals spend hot days hiding under dense brush or near a water source, only heading out to forage in the early morning or late evening. Nocturnal mammals like raccoons, skunks, and opossums already have the advantage of avoiding the sun altogether. But even they make adjustments—limiting movement, resting in insulated dens, and minimizing energy output during stretches of extreme heat.

Opossums, in particular, have it rough: their nearly naked ears, tails, and feet make them vulnerable to sunburn. That’s why they’re rarely seen until after dark, when the temperature dips and foraging can safely begin. However, instead of dashing outside to slather sunblock on your neighborhood marsupials, you can help mammals and reptiles by:

- Adding a water source. Keep the bird bath instructions above in mind and apply them to your water sources at ground level, too. 💧

- Landscape for shade. Keep bushes, trees, and grasses untrimmed, if possible, to offer shade and shelter for rabbits, foxes, skunks, and opossums. If you must mow or garden, keep an eye out for box turtles or other animals burrowed in the cool dirt. 🪴

- Don’t move that rock! Flat stones, logs, and leaf piles may not look like much, but they also serve as essential shade structures. Snakes and lizards in particular might burrow underneath rocks on hot days. 🪨

- Check under your car before driving anywhere to make sure there aren’t any critters under there trying to escape the heat. 🚗

- Watch for heat-stressed wildlife. Animals out in the open mid-day may be heat-stressed or ill. Never approach or offer food, but if an animal looks confused, unresponsive, or is panting incessantly, give us a call. They may need help. ☎️

Three opossums that definitely don’t need help today? That would be Leonard, Barney, and Fiona, our education ambassadors. They’re spending the day snoozing inside our air-conditioned building. Ah, what a life! 😆 We wouldn’t have it any other way.

As temperatures rise, even small efforts can help local wildlife. A little awareness can go a long way! Stay cool out there—and give yourself some credit for thinking of the animals this summer. 😎🍉⛱️ Thanks for reading this month’s Critter Corner from Rockfish Wildlife Sanctuary!

June 24, 2025

Published:

Be the first to comment!