Believe it or not, we still have some baby songbirds in care at RWS! 😲

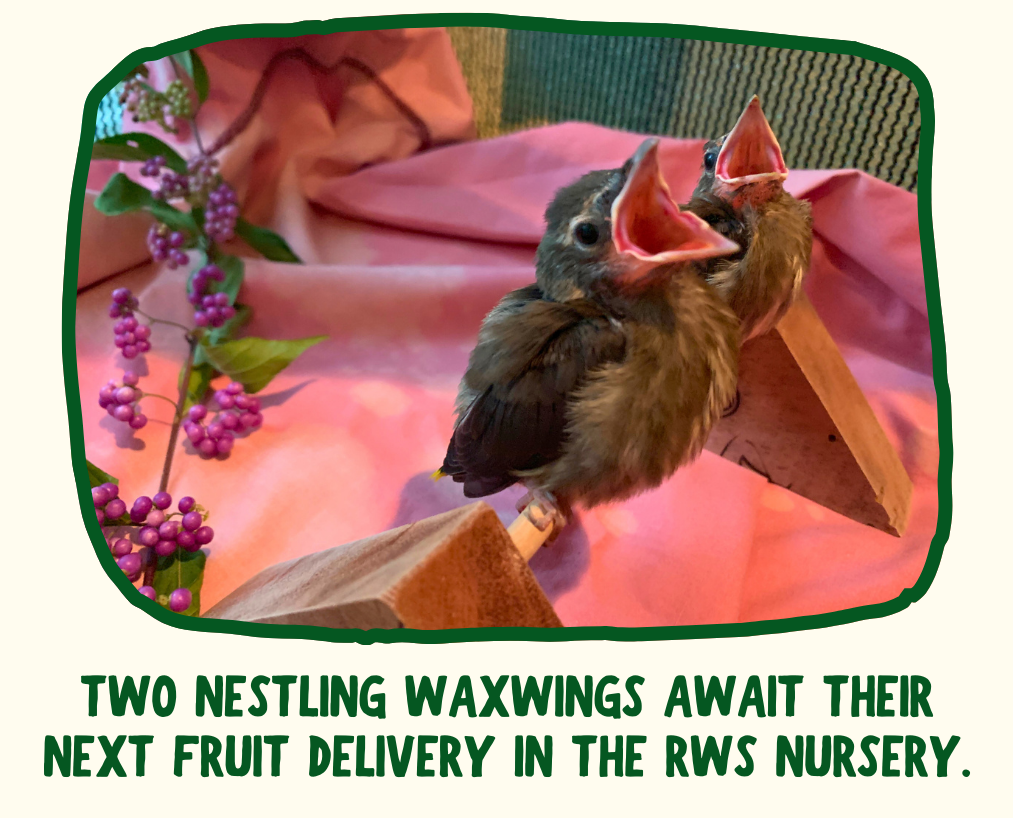

Though we might be growing tired of the “bird timer” telling us to feed them every 30 minutes, we could never be tired of the two birds we have left in our aviary: Cedar Waxwings!

Cedar Waxwings are beautiful, spunky birds that quickly become staff favorites whenever they’re in care. We thought this month’s Critter Corner would be the perfect opportunity to share more about these spirited little masked bandits.

Cedar Waxwings: A (Natural) History

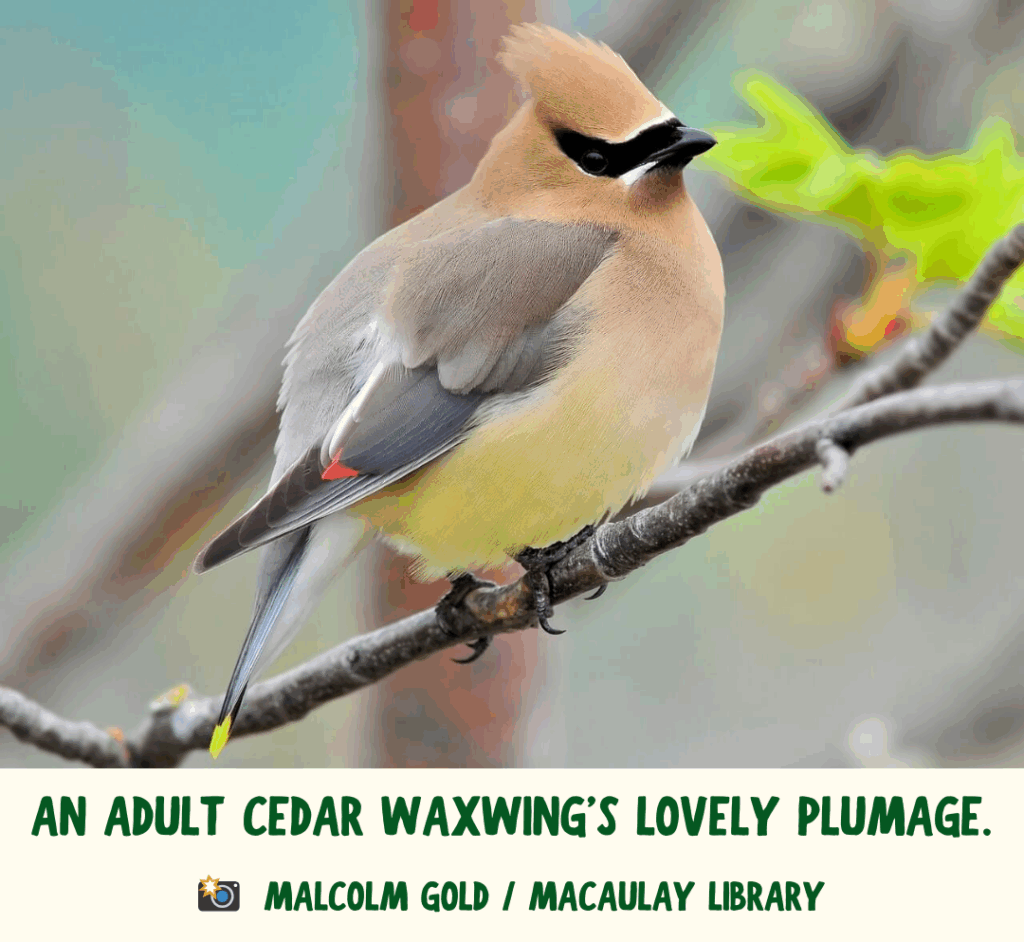

If there were an award for best-dressed songbird in Virginia, the Cedar Waxwing might just win it. These sleek, champagne-colored birds look like they’ve just stepped off a Paris runway, complete with a stylish crest, a black mask, and bright red waxy droplets on their wingtips. Throw in their vibrant yellow tail tips, and you’ve got one gorgeous bird!

Cedar Waxwings are more than a pretty face, though. 💅 Underneath those fashionable feathers is a fascinating natural history.

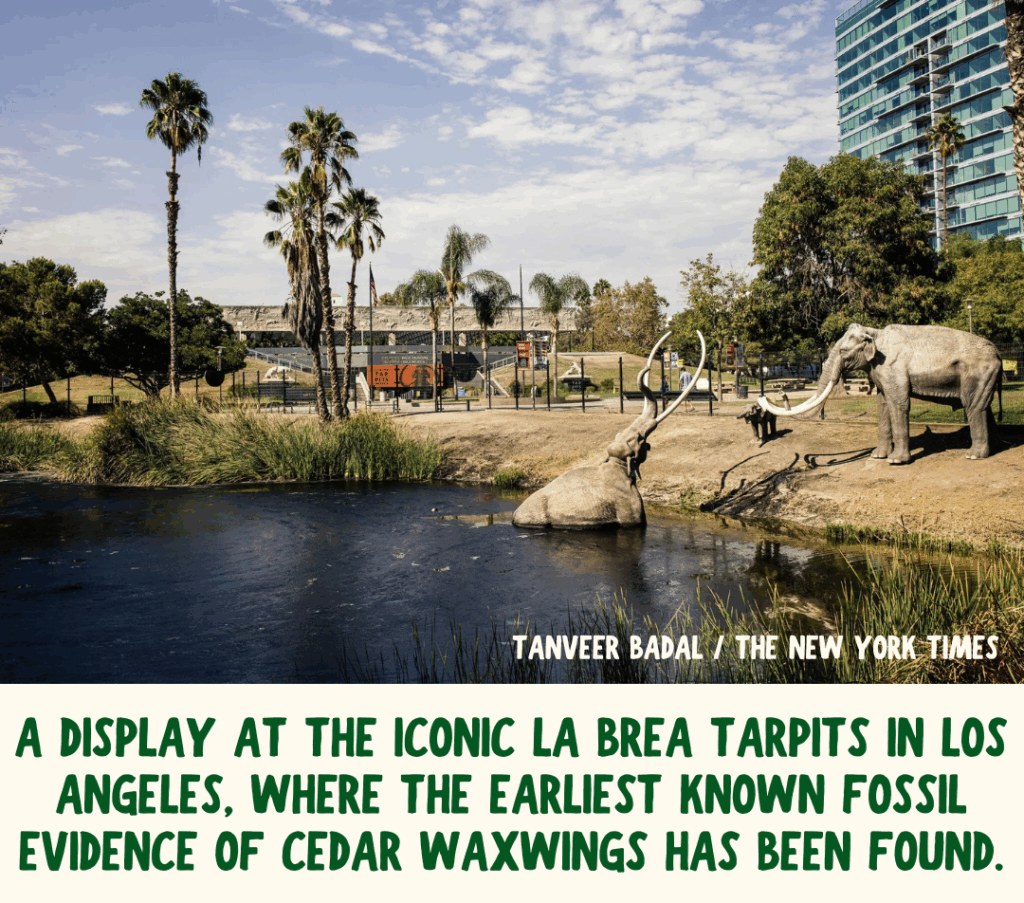

The first fossil record evidence of Cedar Waxwings was discovered by scientists in the early 1900s. Even cooler? They were found in California’s famous La Brea Tar Pits! The fossils dates back tens of thousands of years to the relatively-recent (evolutionarily-speaking) Pleistocene deposits there. While today’s waxwings live alongside animals like raccoons and opossums, these fossilized waxwings were discovered with extinct species like the Columbian mammoths, dire wolves, ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats. 🦣🦥🐺

The Cedar Waxwing’s Latin name is Bombycilla cedrorum, roughly translating to “silk-tail of the cedars.” There are only two other species in the Bombycilla genus: the Bohemian Waxwing (northern Eurasia and western North America) and the Japanese Waxwing (northeast Asia). These three species share a distinct genus given their nomadic lifestyles and highly unique diets. Their lives revolve around one thing that few other birds could exist on: fruit.

Fruit-eating Fiends!

In fact, fruit makes up over 80% of a Cedar Waxwing’s diet! 🫐 They primarily chow down on fruits from red cedars (junipers), wild cherries, dogwoods, blackberry, mulberry, and serviceberry fruits among dozens of other native and ornamental plants. You can spot waxwings most often in shrublands or open forests where these species grow, though they are happy to stop by a fruitful backyard, too! Rather than maintaining specific territories that they defend, they are adaptable little birds that follow the berries. Sounds like a good life to us! 🍇

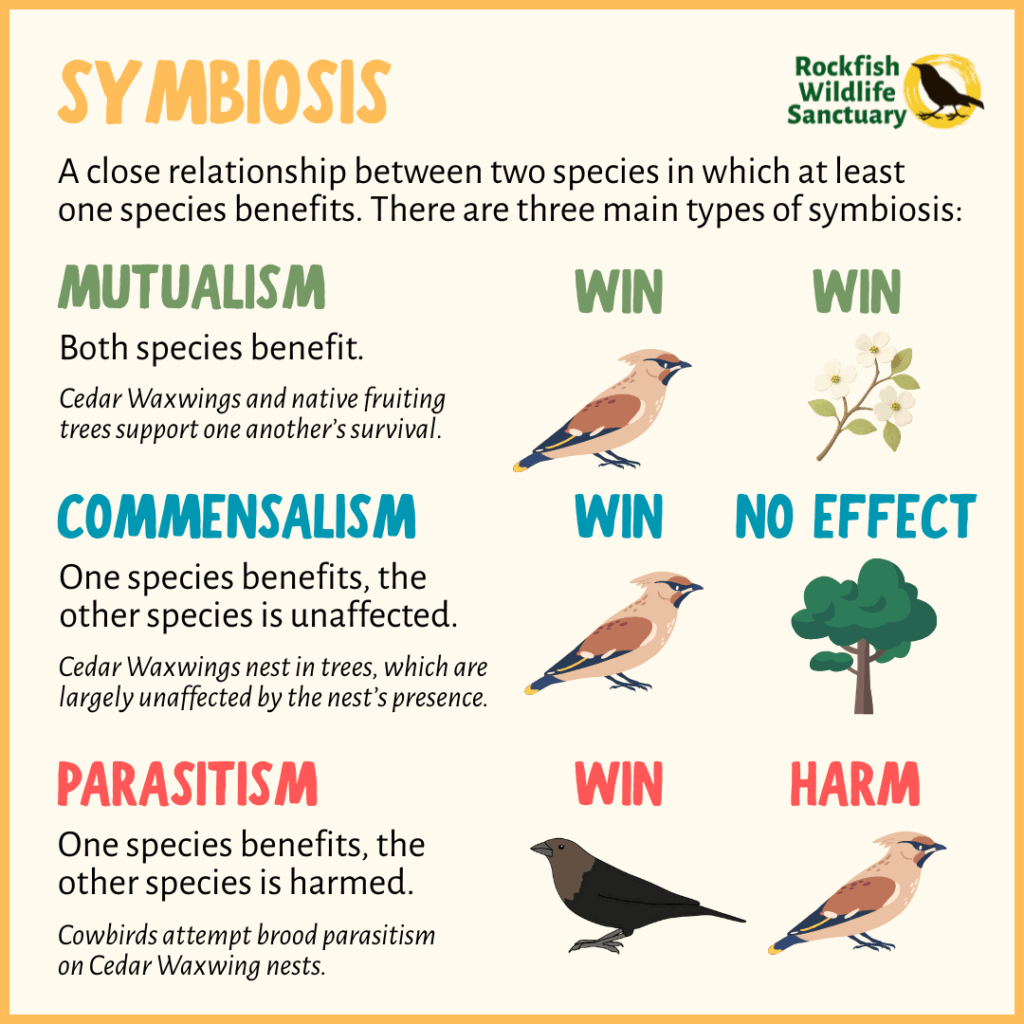

Waxwings are essential members of our ecosystems as a result of their mutualism with native fruiting plant species. ♻️ While most birds who eat fruit will separate out the seed and spit it out, Cedar Waxwings are able to pass berries super fast through their digestive system. This ensures they can eat a ton of berries while dispersing those seeds across wide ranges…through their feces. Charming! As a result, though, waxwings help maintain the very plants that sustain them.

While waxwings have evolved special digestive systems that enable them to eat so much sugar, most birds can’t survive on that much fruit. Take the Brown-headed Cowbird, for example: a native species that relies on parasitism to reproduce. Cowbirds will lay an egg in another songbird’s nest. Often, the cowbird hatchling is much larger than the other hatchlings, thus outcompeting the other babies for the mom and dad’s resources. However, cowbird hatchlings are largely insectivorous and cannot survive on fruit alone, meaning cowbird babies parasitizing a waxwing nest usually don’t survive. 🪺

All of that said, waxwings aren’t solely frugivorous. Insects do make up roughly 18% of the waxwing’s diet, and that’s largely a seasonal change. Waxwings will eat fruit throughout the winter, adding insects into their diet in the late spring and summer when they are most plentiful. Protein-rich insects are important for their nestlings to eat too. Waxwings also chow down on sap dripping from trees as a sweet treat!

Party Animals

This sugary diet can lead waxwings to trouble, though. Waxwings tend to flock together, sometimes hundreds at a time, to spots where lots of berries are growing. Now, we all know that berries don’t stay on a tree forever. As they ripen, many fruits fall to the ground where they’ll begin to go bad…and ferment. If a waxwing chows down on too many fermented berries, the bird can quite literally become drunk from the alcohol! 🍷 Intoxicated waxwings may have trouble perching, flying, and staying upright. Some might even get into fights.

In most cases, the bird will be just fine after having some time to sober up — and local news might have a funny story to report like the one below. However, keep in mind that those symptoms can also indicate head trauma. When in doubt, call RWS!

Mating & Babies

It’s not unusual for Cedar Waxwings to be among the last bird patients in care at RWS since they’re some of the latest-nesting birds on the continent. Cedar Waxwings usually breed from June into August to coincide with berry abundance, though some nests are active into October! Their breeding process begins much earlier, though, as they mingle for mates during spring migration. Scientists think that those trademark waxy red wingtips are a crucial factor for mate selection, since individuals with larger and more numerous red tips tend to have earlier, more successful broods.

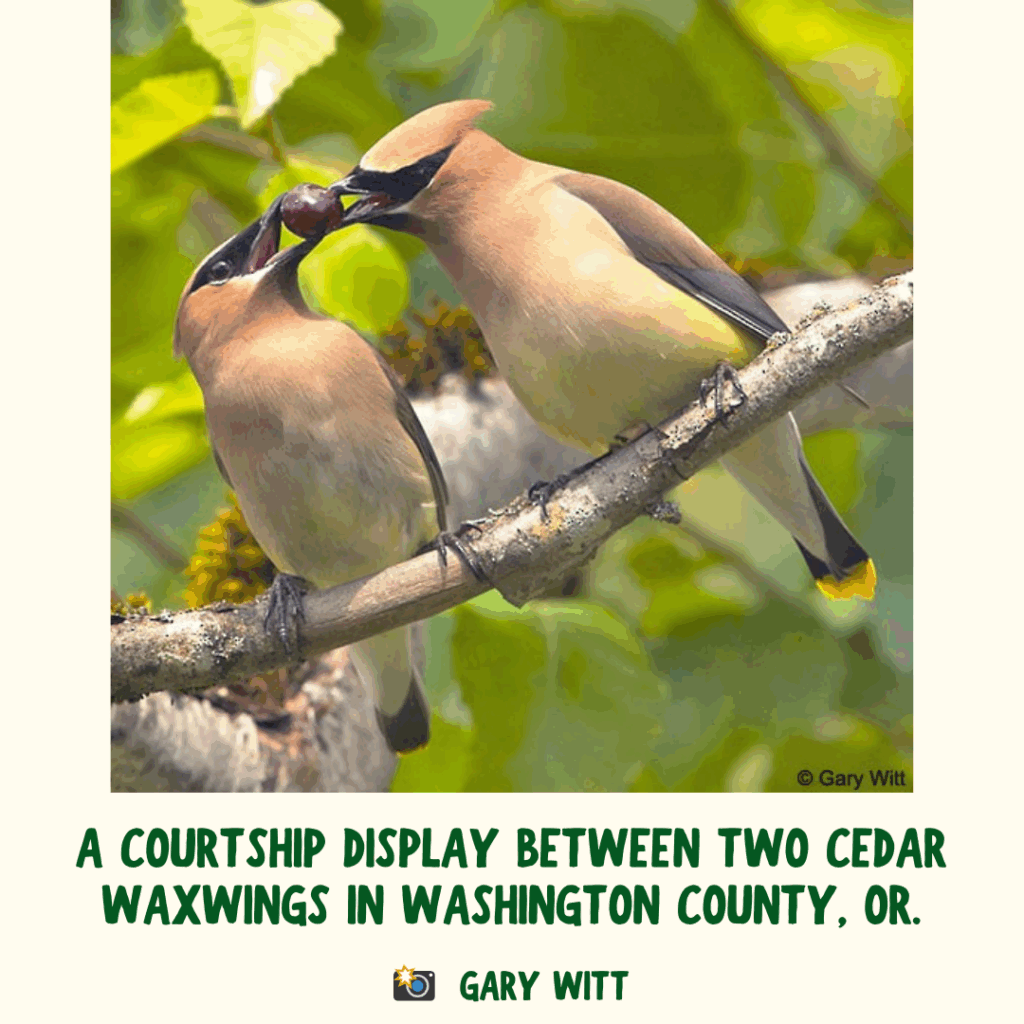

It’s not all about those wingtips, though. The males still need to impress the females to seal the deal. They do so with a charming display called Courtship-Hopping, where the two tentative mates take turns hopping towards one another, sometimes touching beaks. The ritual usually includes passing a small item to the female like a berry, flower petal, or insect. She’ll hop back and forth and pass the gift back to him, repeating the exchange until she finally eats it. That’s love, baby! ❤️

Once a pair has coupled up, they get to nest-building. The female does the bulk of the work. She typically makes over 2,500 trips to and from the nest site during the construction process! Perhaps you felt some pity for waxwings when we discussed cowbird parasitism earlier — don’t worry, waxwings do their own stealing. To speed up nesting, waxwings sometimes pluck materials right out of the nests of other bird species. 😅

Dad (finally) picks up the slack once the babies arrive. Baby waxwings hatch after about 12 days, and typically there are 4-5 per nest. While mom broods over the youngsters, dad gets to work delivering insects for mom and the babies every 15 minutes or so, all day long. 🪰 After roughly three days, the babies are fed progressively more fruit until that’s pretty much all they’re eating when they’re ready to fledge.

Cedar Waxwings in Rehab Care

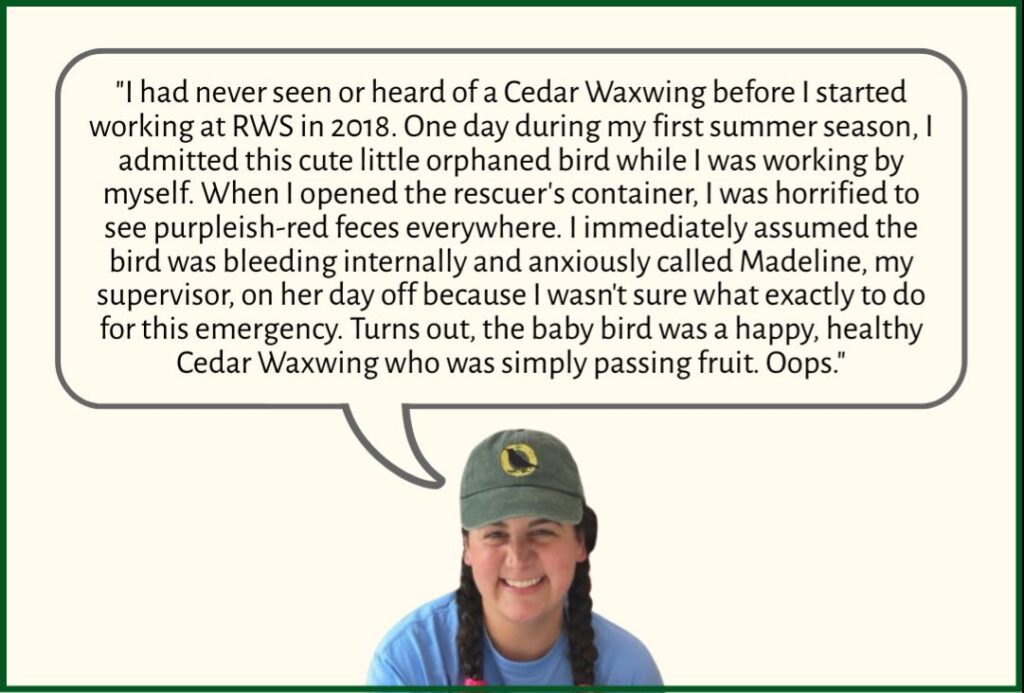

Most of the waxwings we admit for care at RWS are healthy babies, orphaned because they fell from their nest and could not be reunited or because they were “fledgenapped.” That’s when someone assumes a young bird on the ground needs help, when in reality it’s a fledgling who hasn’t mastered flying yet but is still being cared for and fed by its nearby parents. Once they’re in care, though, they tend to leave a mark on our team! Our executive director, Sarah, recalled her memorable first experience with a waxwing:

Given their natural histories, Cedar Waxwings have unique care needs in rehab settings. First, our fruit expenses at the local Food Lion go up considerably. 😆 We can easily clear through dozens of containers of berries in a week. We also try to forage for native fruit along our 20 acres, snipping whole branches of pokeweed berries to gift to our ravenous waxwing clientele. Flight practice is essential as well. While some waxwings are year-round residents, others migrate as far south as Panama and Costa Rica! 🏝️ Our two current waxwing patients are in one of our octagonal flight enclosures, which encourages sustained flight practice and prepares them for a long journey.

Fall Bird Migration

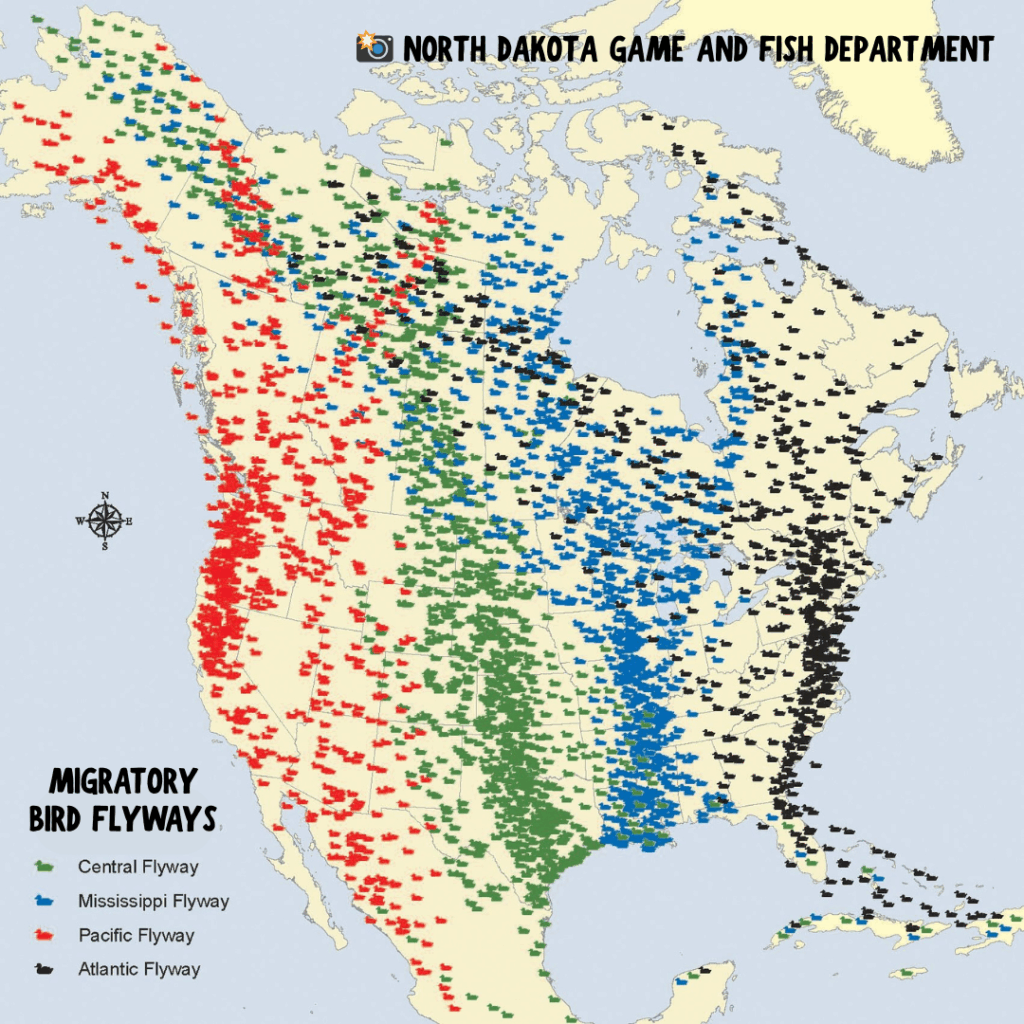

Speaking of migration: peak migration season is still here! ✈️ Millions of migratory birds are flying above us right now as you read this. In fact, about 500 species use the Atlantic Flyway above us each spring and fall on their journeys. Cedar Waxwings are leisurely migrators, stopping to snack on berries throughout their trip. 🍓

It’s easy to support migratory birds like Cedar Waxwings by making some simple changes at home. Incorporate the following tips to help birds stay safe and healthy during their travels.

- 💡 Turn off your lights from 11PM–6AM during migration seasons (March–May and September–November). Most birds migrate during the nighttime, relying on stars to navigate. Artificial light disorients migrating birds, leading to exhaustion and collisions.

- 🐈 Keep cats indoors. Outdoor cats are a leading cause of songbird species decline. Protecting birds also keeps your fluffy friend safer from cars, disease, and predators.

- 🍓 Plant native fruiting trees and shrubs. Species like dogwood, cedar, holly, serviceberry, and winterberry provide essential food for waxwings and other critters.

- ⚠️ Avoid pesticides and herbicides. These chemicals reduce insect populations and can harm plants that produce critical food resources.

- 🪟 Make windows bird-safe. Use approved decals or screens to reduce reflections and prevent deadly collisions.

Thanks for taking the time to learn about some of our fruit-loving feathered neighbors today. You support our work by reading and sharing this Critter Corner!

We hope to see you at our Sanctuary Soirée on November 14th. Check out our event site and sponsorship packages available now! ⬇️

September 29, 2025

Published:

Be the first to comment!