When winter settles in, most of us humans do too.

We enjoy lots of soup, cozier evenings, and perhaps a bit more couch time than usual. 📺 🛋️ Our wild neighbors adapt accordingly. For many of the critters that don’t migrate south for the season, winter means totally powering down.

You’ve probably heard the term hibernation before, but you might be surprised to learn that few animals are true hibernators! In this month’s educational Critter Corner, we’re clearing up the confusion and meeting the creatures that truly master the art of winter rest…and maybe taking a little inspiration from them. Netflix and naps, anyone? 😴

Metabolism: The Basis of Hibernation

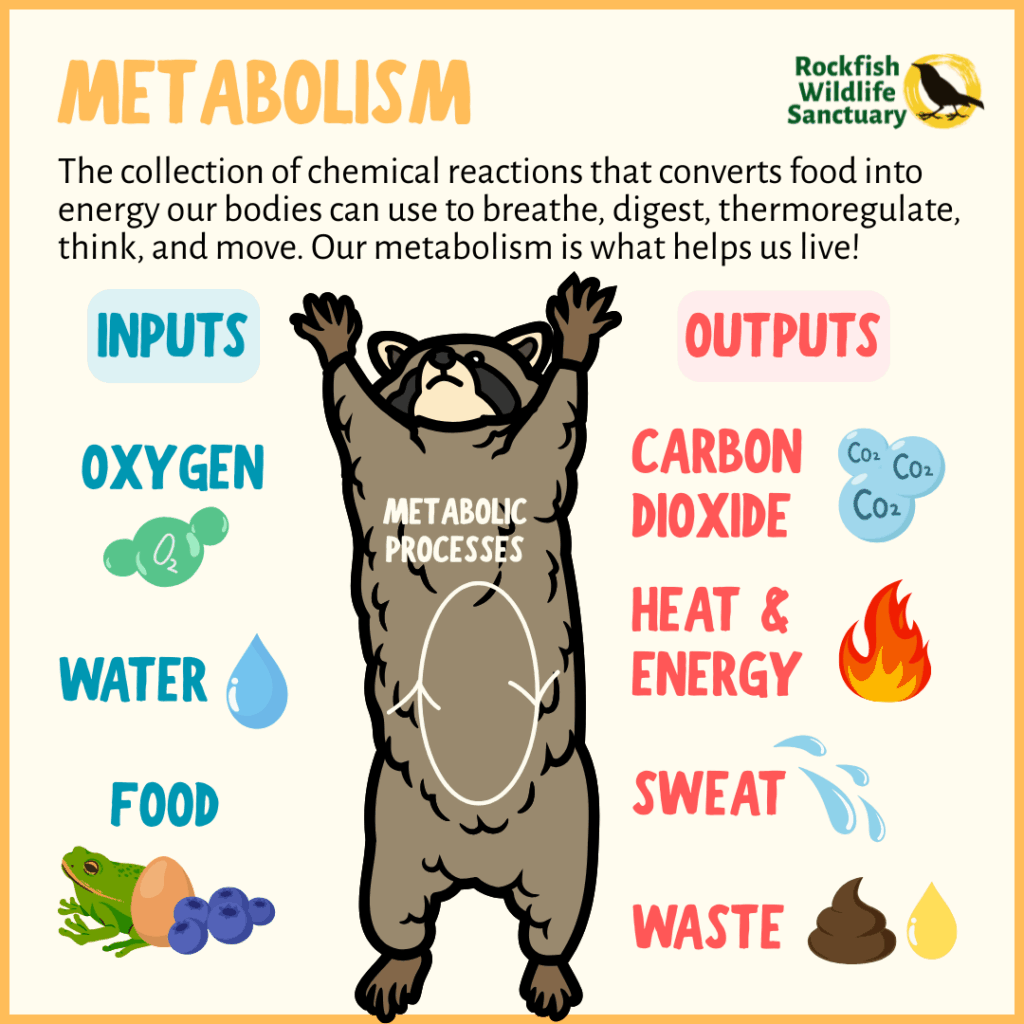

Let’s start by chatting about metabolism, since that’s essential to understanding how hibernation works. Metabolism is simply the collection of chemical processes that keep a living creature alive. It’s how food is turned into energy for breathing, digestion, movement, growth, and maintaining body temperature. Pretty important stuff! Your metabolic rate refers to how quickly your body burns through that energy to keep everything running.

When animals “slow down” for winter, what they’re really doing is lowering their metabolic rate. This means means their bodies burn energy far more slowly. Less energy burned means less food needed and, ultimately, that results in better odds of surviving winter when food is scarce.

So with that in mind, what does hibernation really mean?

True Hibernation

True hibernation isn’t just a long nap, like cartoons make it out to be. In reality, it’s an extreme physiological state during which animals drastically slow down their metabolic rate so they can survive winter’s lack of food.

Hibernation is a voluntary process that’s cued by chemicals, including the aptly named Hibernation-Induction Trigger (HIT) compound. Scientists think that a range of factors like shortening days and colder temperatures cue the release of HIT, which is similar in chemical structure to an opioid. 😴 In fact, transfusing blood from an animal in natural hibernation cues hibernation in otherwise active animals!

Once animals enter hibernation, they rely entirely on fat stored in the fall and may remain dormant for weeks or even months at a time. True hibernators experience:

- 🌡️ A dramatic drop in body temperature (sometimes just a few degrees above freezing)

- 🫀A slowed heart rate and breathing

- 📉 An overall metabolic rate reduced to about 6% of normal on average

If humans did this, we’d take roughly one breath per minute, our hearts would beat just four or five times per minute, and we’d survive on about a banana’s worth of calories per day. For us, that would be dangerous…if not fatal. For true hibernators, it’s life-saving!

Who really hibernates?

There are surprisingly few warm-blooded species that truly hibernate. (More on our cold-blooded friends in a bit!) These hibernators include…

Groundhogs:

Groundhogs are the poster children of hibernation. Their heart rate can drop from about 80 beats per minute to as low as 5, and their body temperature can plunge from around 99°F to 37°F. A single breath can last them several minutes. In Virginia, groundhogs typically remain in this state for two to four months depending on winter conditions.

Non-Migratory Bats:

While some bats migrate to get away from the cold, those who don’t need to survive the winter without their favorite insects available to snack on. Species like Big Brown Bats hibernate in caves and rock crevices where temperatures remain stable. Living almost entirely off stored fat means winter disturbances (due to diseases like White-Nose Syndrome, for example) are extremely dangerous. Each unnecessary wake-up burns valuable energy they can’t easily replace. (Learn more about White-Nose Syndrome and native bats in our recent blog post.)

Ultimately, true hibernation is like switching a body into extreme power-saving mode – not sleep or standby, but more like a system shutdown with essential processes only.

Hibernation Lite

Here’s where the mythbusting starts: we made sure to write “true” hibernators above because many animals people think of as “hibernating” are actually experiencing…drumroll please…torpor. 👀

Torpor is a temporary, involuntary response to cold that lasts hours or days rather than months. Metabolism slows, body temperature drops, and energy use decreases – but not nearly to the extreme of true hibernation. On average, metabolic rate during torpor drops to about 35% of normal.

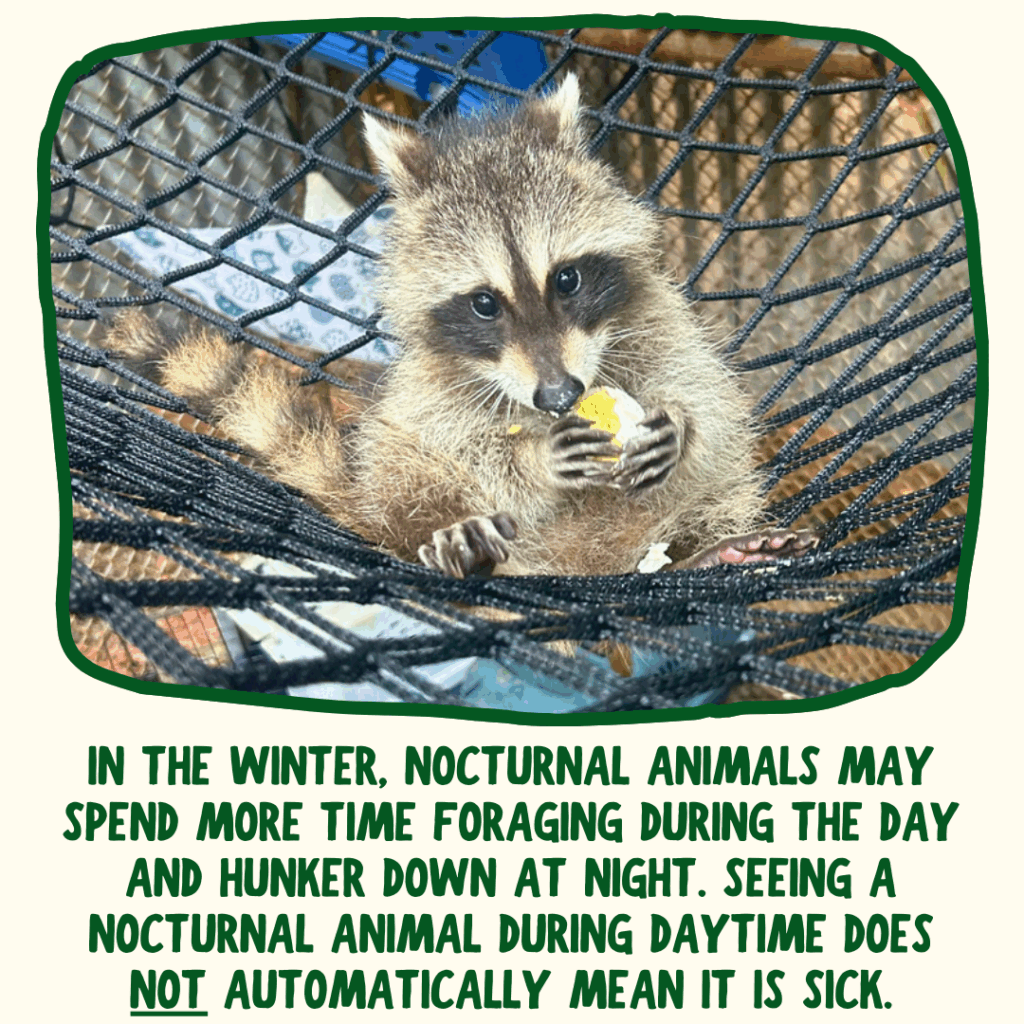

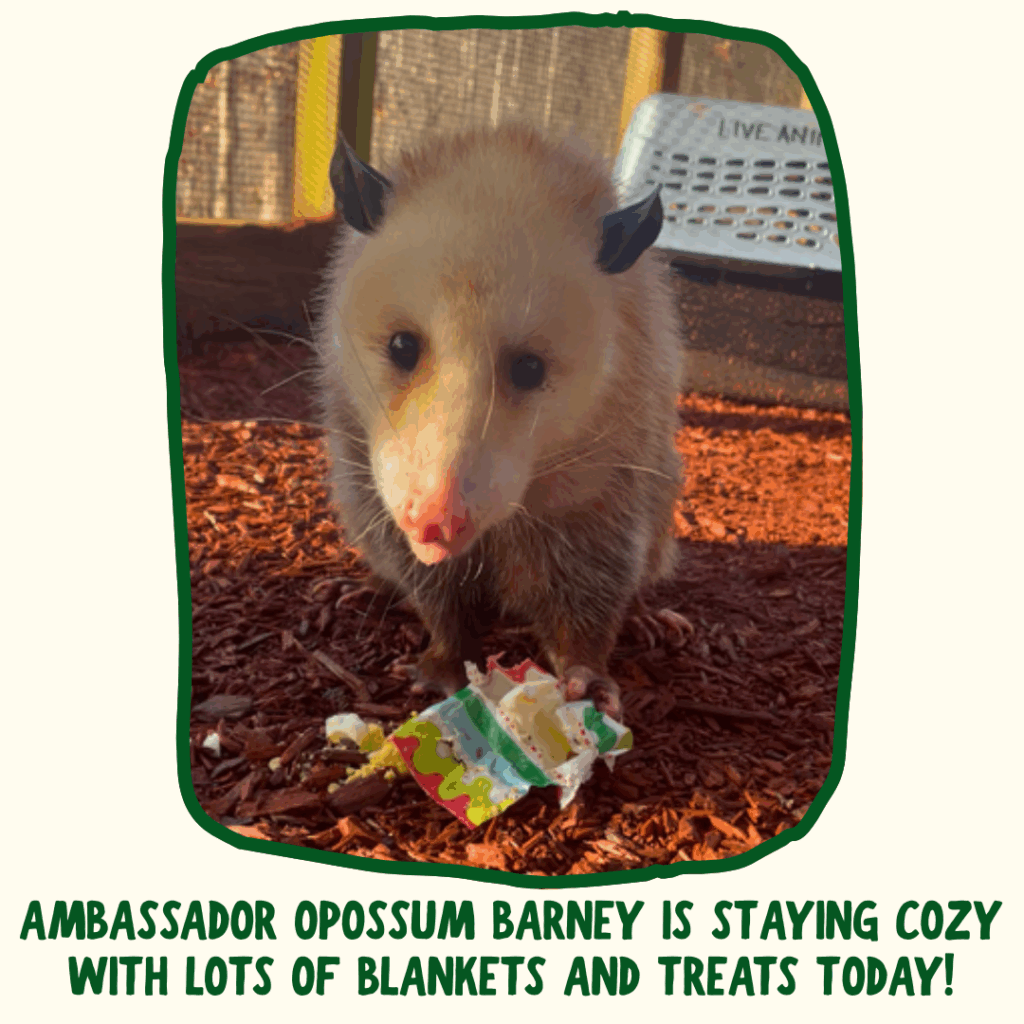

Torpor helps animals conserve energy without committing to a months-long shutdown. This flexibility works especially well in Virginia, where winter weather can swing wildly from week to week. Animals that experience torpor include raccoons, skunks, opossums, and black bears. 🦝🦨

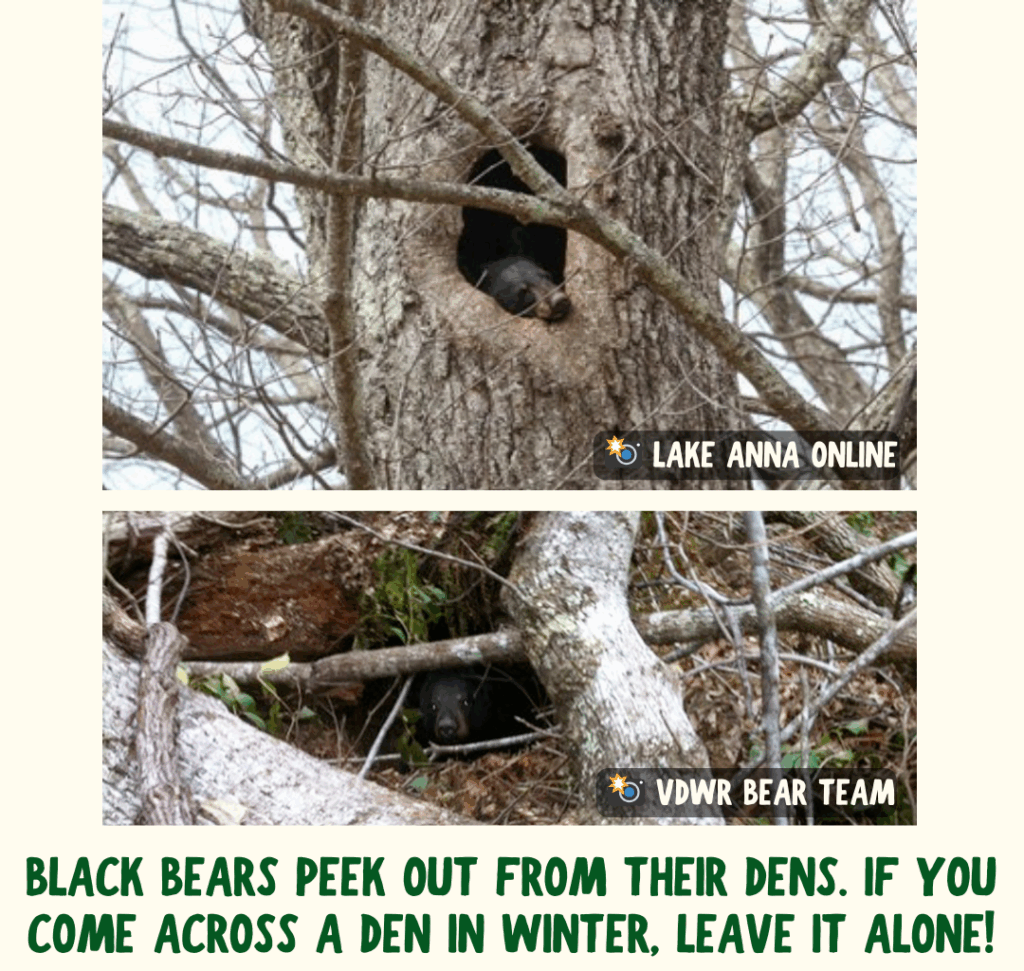

Yep, that’s right – black bears are not true hibernators! A bear’s body temperature only drops slightly, and they can wake fairly easily if they detect danger or temps rise enough to forage. Female bears even emerge from torpor to give birth in mid-January or so. 🐻

True Hibernators Headscratchers

And yet, there are some critters whose sleepy winter behavior we still don’t totally understand. 🤔

Take the Eastern Chipmunk, for example. Their metabolic rate slows drastically, like you would expect from a true hibernator. Their heart rate drops from 350 beats per minute to just 15, and their body temps fall from the 90s to the mid-40s. Sounds like hibernation, right? Well, they wake up every few days to snack and relieve themselves…which sounds a lot more like torpor! These blurred lines are proof that nature doesn’t always fit neatly into our definitions.

Brumation

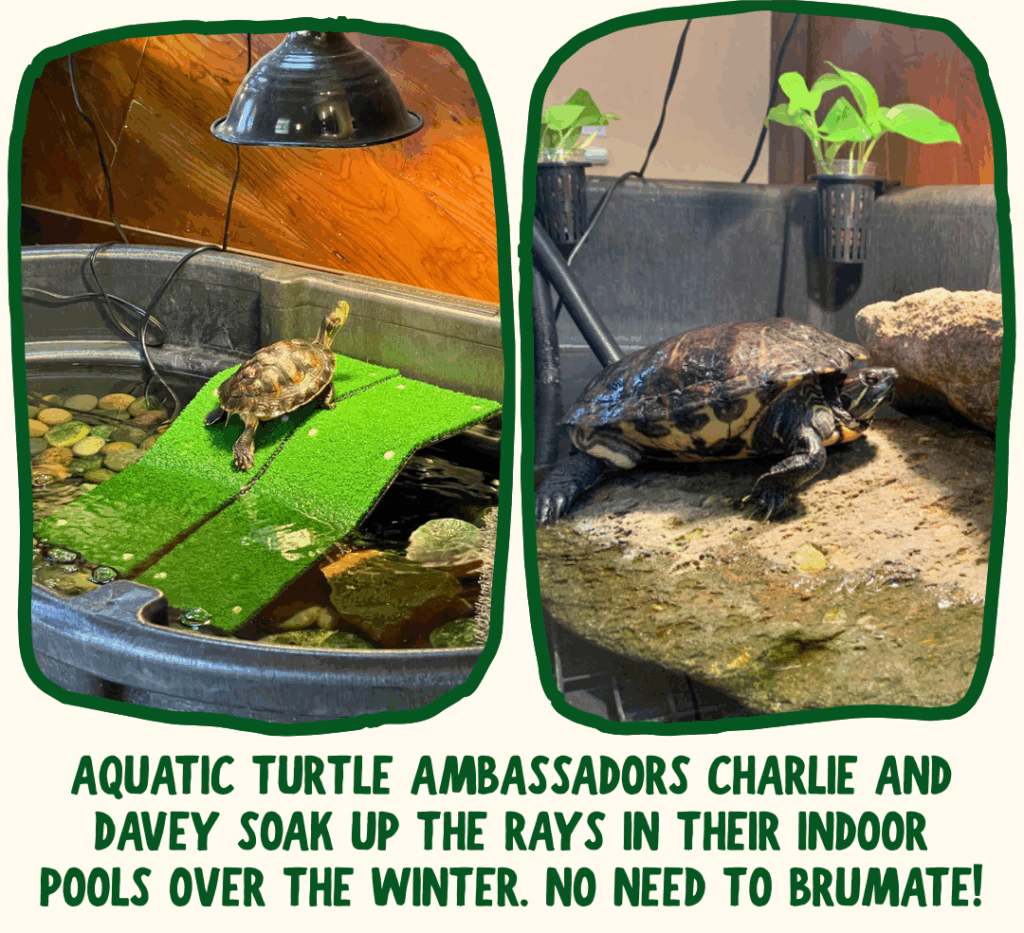

Now what about our cold-blooded neighbors? They slow down, too! However, their version of hibernation is called brumation. 🐸🐢🐍

Because reptiles are ectothermic (cold-blooded), their body temperature depends on the environment. As temperatures drop, their metabolism naturally slows. Virginia’s turtles, snakes, lizards, and frogs burrow below the frost line, beneath leaf litter, or into the muddy bottoms of ponds and streams.

During brumation, bodily functions slow astoundingly. For example, a typical brumating aquatic turtle’s body temperature on average will drop to just 39°F with blood oxygen levels dropping to near zero within hours of being submerged. 😱 That oxygen level would kill a human within three to four minutes…yet some turtles can survive for three to four months like this. Nature is bonkers.

Putting It All Together

Why does all of this matter? Understanding these winter survival strategies helps us recognize when a wild animal truly needs help! 💪

These winter slow-downs are finely tuned to temperature, daylight, and food availability. Warmer winters, sudden cold snaps, and human disturbance can all disrupt the delicate balance animals rely on to make it to spring.

If you encounter wildlife in winter that seems out of place or distressed – especially bats, turtles, or other animals that you’d expect to be dormant – that’s your cue to call us at RWS. ☎️ Rescuing the wrong animal at the wrong time can do more harm than good, and we’re here to help you assess the situation.

We hope this Critter Corner helped clear up the mystery of who’s truly hibernating, who’s just dozing, and who’s (quite literally) chilling underground. Thank you for reading! 💙

December 17, 2025

Published:

Be the first to comment!